The whole world's gone nuts

Indignity Vol. 4, No. 194

NATURAL HISTORY DEP'T.

It's a Big Year for Acorns, Again

ACORNS ARE RAINING down on New York City. On a quiet Saturday morning in October, waiting for the uptown M10, I could hear the tocking of stubby little acorns falling from the towering pin oaks of Central Park West to land on the pavement of the bike lane. Blue jays were darting around up among the branches. On the way home there were still more blue jays and still more acorns, the birds chasing around in circles in the top of a smaller oak tree as the nuts plopped down.

The name for this event is a "mast year." The white oaks are at it too, scattering their long, burnished acorns—the size of a thumb joint—on the sidewalk on the cross streets, or sending them ricocheting off the roofs of parked cars. Acorns roll around in circles or crunch underfoot or settle into the gutters and pavement joints.

The word mast goes back to Old English. It refers to the nuts and fruits of the forest, on which commoners could turn loose their pigs to fatten them up, at a scheduled time of the autumn. Some years the mast is sparse, and some years the trees all synchronize and drop their nuts in abundance, across hundreds of miles. No one knows why; it's not even clear, ontologically, whether a mast year is something that trees do, or something that happens to the trees, or something in between.

One way of describing what happens in a mast year is that the trees drop so many acorns that the acorn-eating animals can't possibly consume them all. And after those acorn-eaters, glutted on the bounty, produce lots of young, the next fall's supply is scant, so that the enlarged population starves and dwindles, so that in some future year the oaks are ready to strike again. The cycle is irregular enough—generally two to five years—that the acorn-eaters can never get in sync with it.

The ecological effects are real. Researchers have found that deer and mice will feast on the acorns and breed; ticks will feast on the deer and mice and breed in turn; Borrelia burgdorferi bacteria will propagate among the deer and mice and ticks together; cases of Lyme disease in humans will increase. In starvation years, the mice will decline, spongy moths will escape being eaten by the mice, and the spongy moth caterpillars will attack the oaks.

But are the trees doing it on purpose? Trees do communicate with each other, to an ever more thoroughly documented extent, via airborne chemical signals or messages passed through underground fungal connections. "Whether or not that means that all of the oaks across the Northeast are in a group chat, it's hard to say," Melissa Finley, the Thain Curator of Woody Plants at the New York Botanical Garden, told me on the phone.

It could be, instead, that the variation comes from whether springtime conditions are better or worse for windborne pollination among the trees. "It's thought that some of it might just have to do with high pollination success," Finley said. "So not so much the trees' kind of planning for being eaten, but just whatever circumstances are creating optimal pollination and fertilization and having adequate water and sunlight, a really good year for sort of carbohydrate manufacturing."

Scientists have also suggested that rather than simply making it easier for trees to pollinate, leading to more fruit, favorable springtime weather might itself be a signal telling the trees to all switch over to maximum production. Mast years aren't a matter of the trees flourishing in general; they appear in tree rings as years of limited growth. Instead of getting thicker and taller, when a mast year comes, the trees push their effort out to the ends of the branches, and thence to the ground.

When I was a child growing up in a house in the woods, shooting acorns around the yard with my wrist rocket, I never paid attention to the fact that some years had more ammunition lying around that others. Acorns lying along Broadway, outside Absolute Bagels, are harder to take for granted.

Noticing it isn't the same as understanding it, though. For one thing, not all the acorns falling right now grew at the same time. The pin oaks are in the group of red oaks, which take two years to develop acorns. The white oaks grow their acorns in a single year. Yet they're rattling down together this fall. Is the two-year cycle somehow aligned with the one-year cycle? The question is even harder to answer because—contrary to the whole premise of mast years being intermittent events to thwart nut-eaters—2023 was also a mast year.

What do back-to-back mast years indicate? "I think you could make maybe a tenuous connection to climate change," Finley said. "But even whether having two in a row is going to be bad or not—I think we can kind of assume that it's a stressor, but if that will be noticeable or measurable down the line, it's hard to say. Whether or not we can anticipate these alignments increasing is hard to say. It's still quite a mystery."

SIDE PIECES DEP'T.

Over at Defector, I wrote about the election:

So I lined up and voted. I cast my first-ever presidential general election ballot for Bill Clinton, well aware that he'd made the racist human sacrifice of Ricky Ray Rector to get there. Regretting or deploring some of the choices Harris has made in building her coalition isn't the same as believing she's not running to win. I never want to be on the same side of anything as Liz Cheney, much less Dick Cheney, and I'm sure the Cheneys would feel the same way about me. Unfortunately, one of the live issues in this particular election is "Was it good or bad for a mob to smash its way into the Capitol to try to steal the 2020 election for Donald Trump?"—and Liz Cheney did stake her entire otherwise reprehensible political career on taking the correct side of that question. Beating back the mob for good means isolating and marginalizing everyone on the other side as much as possible, and that, in the world of 2024, means suffering testimonials from the Cheney family.

WEATHER REVIEWS

New York City, November 4, 2024

★★★ A pink glow shone from the dawn sky and then faded out. A dampness was on the air out by the garbage cans before the trash truck arrived. The sun kept faring better than the forecast had called for, swelling into interludes where the street trees sent gold light pouring in the windows before it subsided again. Loose-shaped light gray clouds moved quickly below clumped and furrowed silvery ones. The descending sun still looked white but it sent orange tones over the jumbled sky. A heavy throbbing heralded a tiltrotor Osprey chugging north against the churning piles of cloud.

EASY LISTENING DEP'T.

HERE IS TODAY'S Indignity Morning Podcast.

Click on this box to find the Indignity Morning Podcast archive.

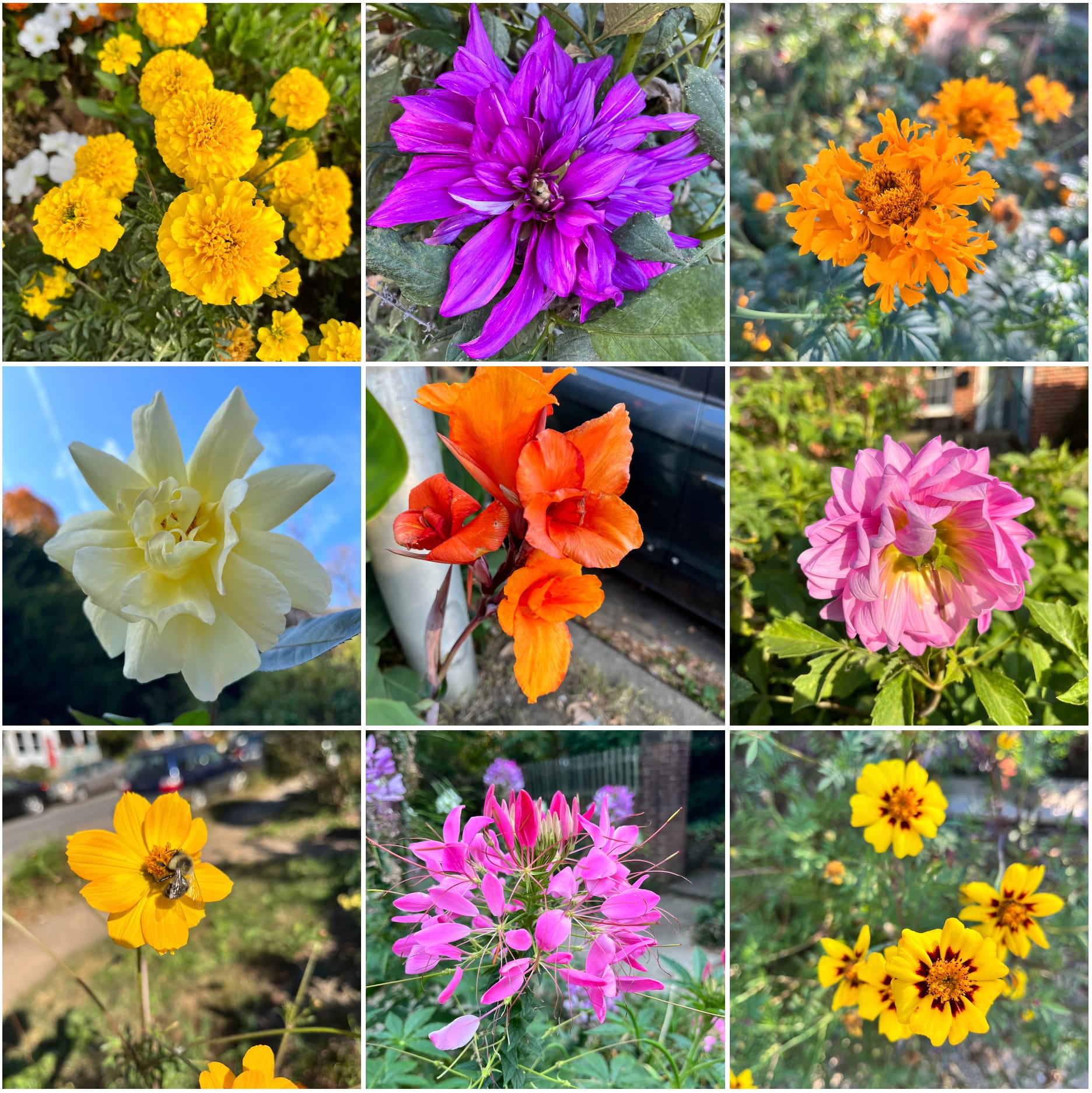

VISUAL CONSCIOUSNESS DEP'T.

Late Bloomers

More consciousness at Instagram.

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP'T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS in aid of the assembly of a sandwich selected from Benson Woman's Club Cook Book, Containing Over Four Hundred Of Our Own And Our Friends' Choice Recipes, collected and compiled by Benson Woman's Club, published in 1915, now in the Public Domain and available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

ENGLISH WALNUT SANDWICHES.

Chop fine 1 cup of English walnut meats and add enough cream cheese to make a moist paste. Add salt and a dash of cayenne pepper, and spread on thin slices of bread which have been lightly buttered. The slices of bread may be round or any fancy shape desired.

—Mrs. J. V. Starrett.

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, be sure to send a picture to indignity@indignity.net.

MARKETING DEP'T.

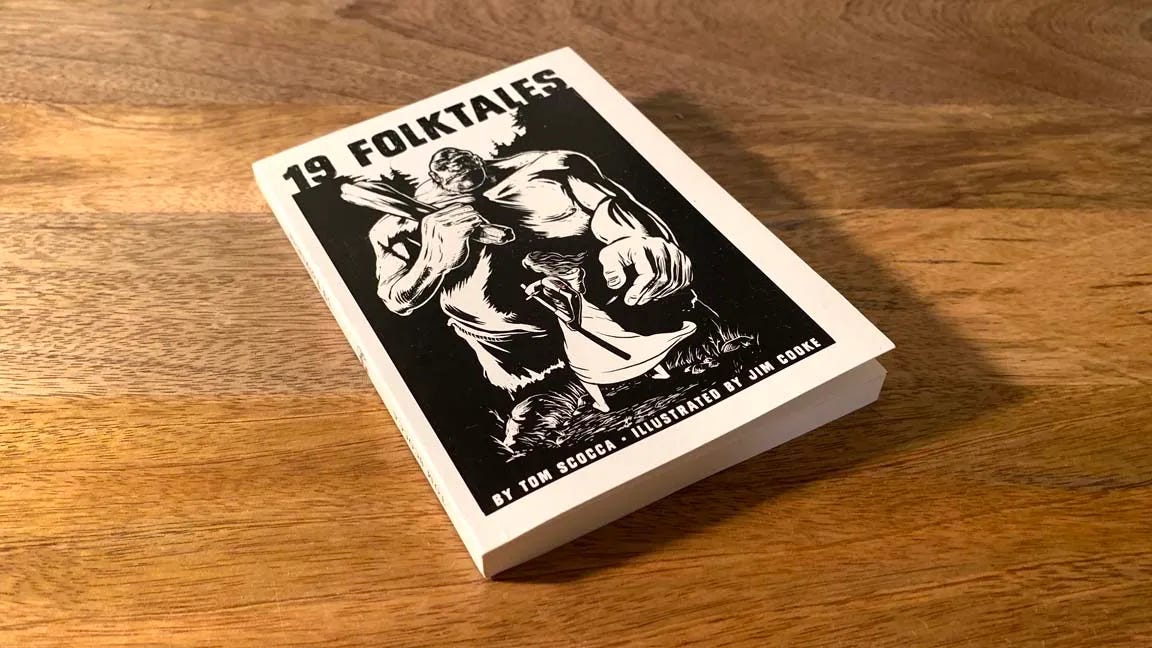

We are down to FIVE REMAINING COPIES of the second printing of 19 Folktales, still available for gift-giving and personal perusal! The daylight is vanishing and so are these stories!