INDIGNITY VOL. 3, NO. 57: Masterpiece theater.

ART APPRECIATION DEP'T.

Meeting Michelangelo's Little Boy

I WAS NOT prepared to see Michelangelo’s David, but right up until the moment the tour guide led us around the corner into the gallery, I hadn’t thought I would need to be prepared. It’s the David, what was there to know? Western Civilization! The David was all over the t-shirts and souvenirs outside, sliced up and decorated and decontextualized until it was context itself—or background noise, Italy's version of the Statue of Liberty or I [HEART] NY.

But it transcended Italy. It was everywhere, always, like the Mercator projection. Wasn't it? Someone had only just been in the news, in America, for getting fired after showing her Christian school students a picture of it, a story built of familiar components: resurgent philistinism, the indisputable canon, that famous bare penis. (You could buy a scarf with the penis printed on it out in the vendor stalls of Florence, alongside the bootleg soccer-club merchandise.)

Going to see the David was one of those extended-family vacation ideas that presents itself as a fait accompli. We were not in Florence, we were all staying in an Airbnb in a remote hamlet for the sake of the Tuscan country experience, but Florence was a one-hour drive and so everyone was driving to Florence, and when you go to Florence, you visit the David.

By the time we arrived in line outside the Galleria dell'Accademia, I was in anything but a receptive frame of mind. The only thing I had learned in advance about going to Florence is that you weren't supposed to drive there, that the old city center had heavy fees or fines for bringing a car into it. I was not in charge of making the parking reservations, though, and the parking reservation was in the old city. We'd approached the destination on Google Maps on ever less propitious-looking streets, squeezed in by walls, and then Google Maps had sent me across the river—the Arno—into the heart of the old city center.

I didn't know what else to do. The streets were even narrower, and full of pedestrians—strolling family groups, people with rolling suitcases, everything. At some crucial but confused point, as I crept along in the Fiat, yielding to everyone, I missed or misunderstood a sign and Google Maps sent me through an intersection that changed the roadway from predominantly pedestrian to absolutely pedestrian, prohibitively pedestrian. On the screen, Google's version of the street was full-speed-ahead blue; out the windshield there were anti-car planters in the roadway. I was the idiot American with a car where no car belonged, and realizing that fact did nothing to help me get the car out of there.

Eventually, as I inched along, burning with shame, two grim Carabinieri confronted me, to tell me what I already knew. One of them tried to describe a list of turns for me to take, then glanced at the car's information screen and resignedly told me to just go ahead and finish doing what Google Maps was telling me to do. On the final leg to the garage, the eleven-year-old, in the back seat, said he couldn't wait to tell everyone at school about how we became international criminals.

As we handed over the money for our tour guide—a form of ticket scalping, basically, as I understood it—I mentally added in a three-digit fine in Euros, once the authorities finished tracking us down through the rental-car company. Everyone got dorky tour-group sticker-badges and dorky radio receivers on lanyards, with dorky over-the-ear earpieces. The Achilles tendon on my clutch foot was throbbing. Somehow no one had left enough time for lunch.

Our tour guide, who introduced himself as Claudio, lined us up and then kept using the earpiece radio to gently apologize for the fact that other tour groups kept going in ahead of us, as our scheduled time came and went. There was a delay at the metal detectors, he said. Fine, whatever, the time and the money were both sunk. We would go in and give the David the appropriate degree of admiration for being what it was, and then it would be over.

Once we were inside, though, we couldn't quite get to the David. Claudio, with winning candor, had warned us there wouldn't be much else to see—the Medicis had taken all the good paintings, and they'd ended up in the Uffizi. The Galleria dell'Accademia, he said, just had the David, a few unfinished Michelangelos to go with it, some historic musical instruments, and a collection of technical specimens of painting and sculpture, uninspired academic work. Still, before we could make it to the main event, we needed to get through a quick biography of Michelangelo's early years, with a look at pictures of his Vatican Pietà on Claudio's iPad. Claudio zoomed in to show where the young Michelangelo, in a fit of anxiety about getting the recognition he deserved, had chiseled his signature into Mary's garments.

And now, Claudio said, it was time to see "the little boy."

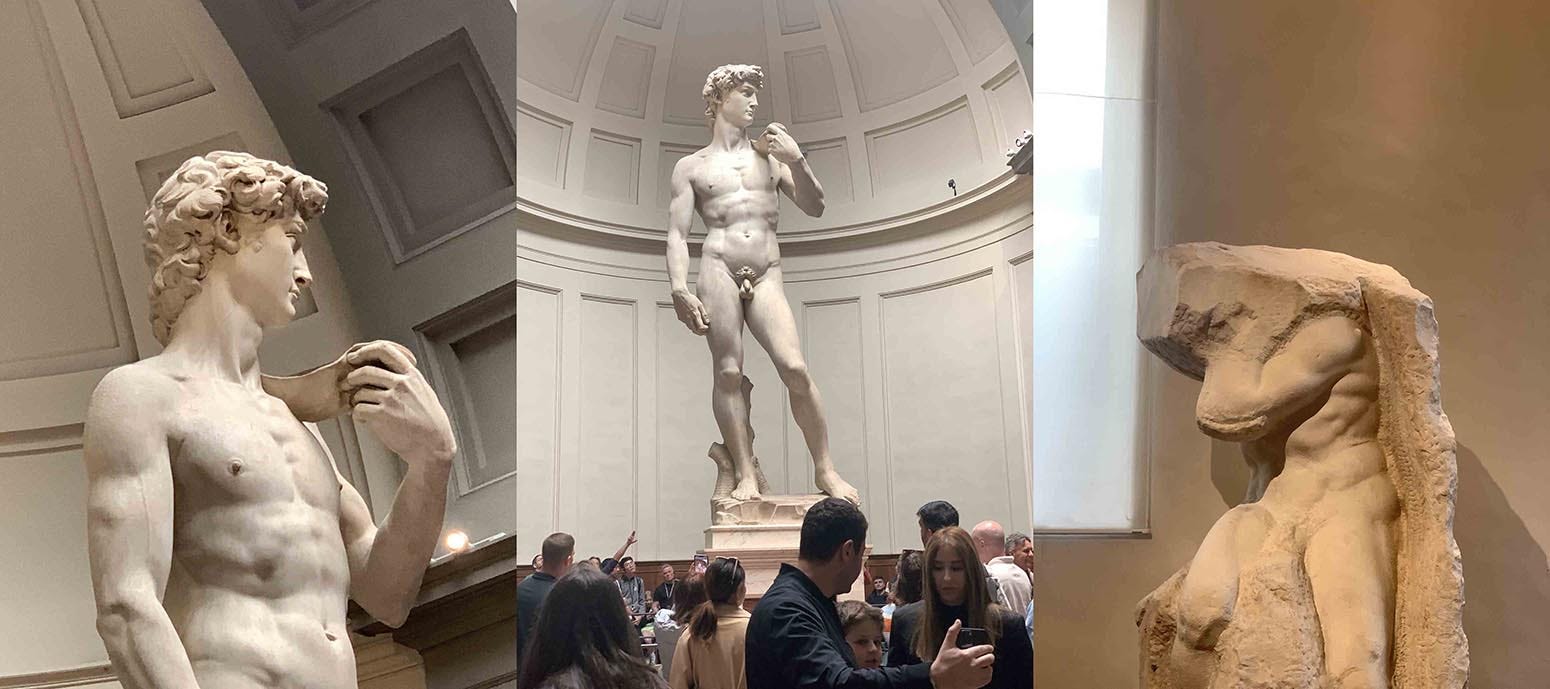

I was puzzling over that turn of phrase, the sudden tenderness—and irony?— behind it, when we rounded into the hall. There, in the distance, gray-white under a grayly skylit dome, was the little boy.

Catching sight of it felt like being in a disorganized crowd that suddenly starts to surge together, or being at the wheel when a car hits a patch of ice. Whatever I'd been anticipating was no longer relevant. Something else had taken over.

I had been wrong, I realized, about a very basic thing: I knew the David was larger than life, but in my mind that meant maybe eight feet tall. Its beauty, not its size, was the thing it was famous for. This David, the physically present David, was 17 feet tall. It was an immense piece of marble, and the combination of that scale with the delicacy of the work was vertiginous, and that was nowhere near the most unsettling thing about it.

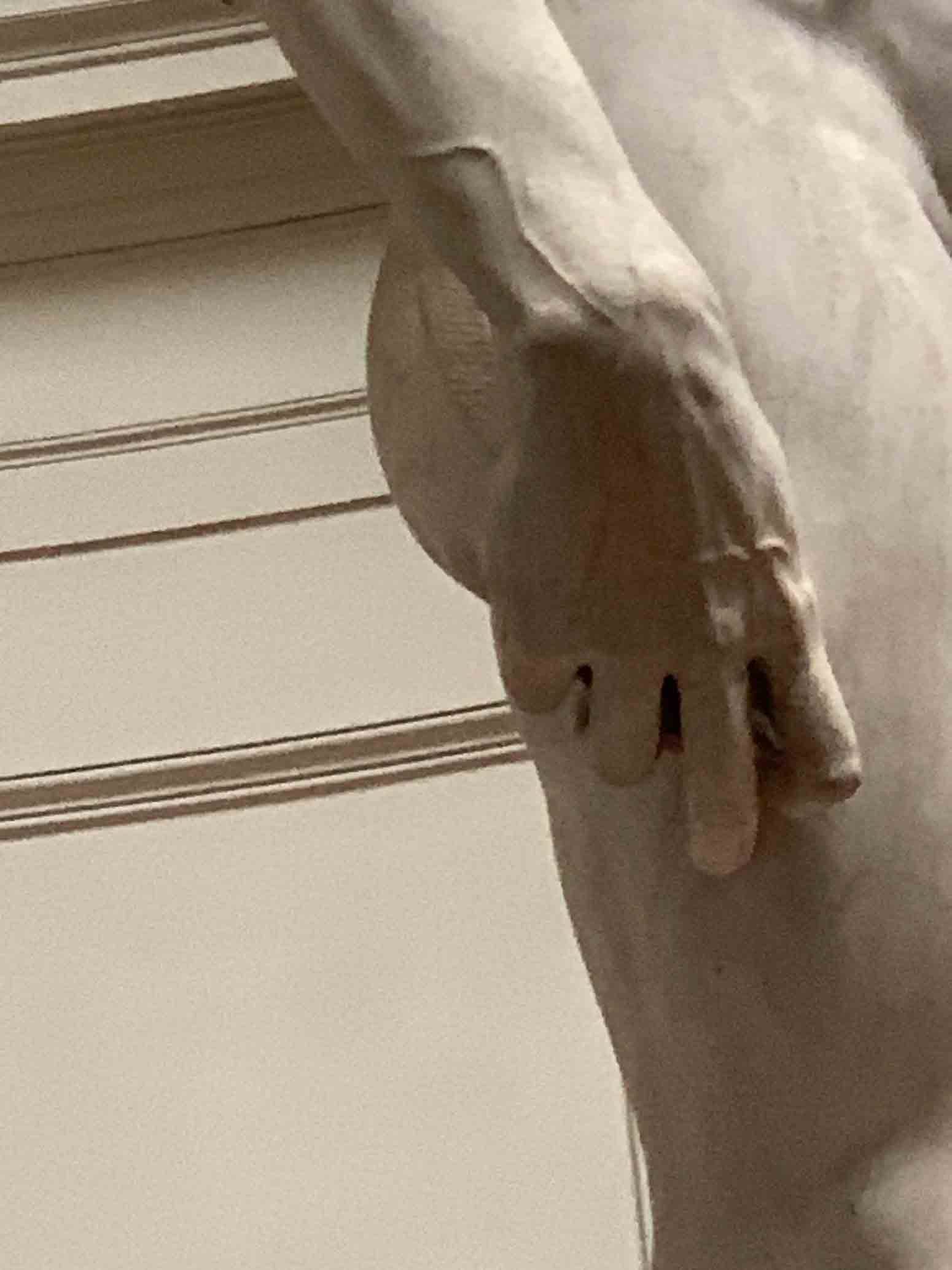

The most unsettling things about the David were, first of all, that it was overwhelmingly strange. Claudio insisted that we stop and look from a distance before moving closer, and note the unusually large hands and head. Possibly, he said, Michelangelo had exaggerated them as a device for perspective, for the statue's original planned placement up on a roof. Possibly he had some other artistic purpose. Either way, the proportions were uncanny, beyond human. Michelangelo unquestionably knew how to make something look perfect, and he went for something else instead.

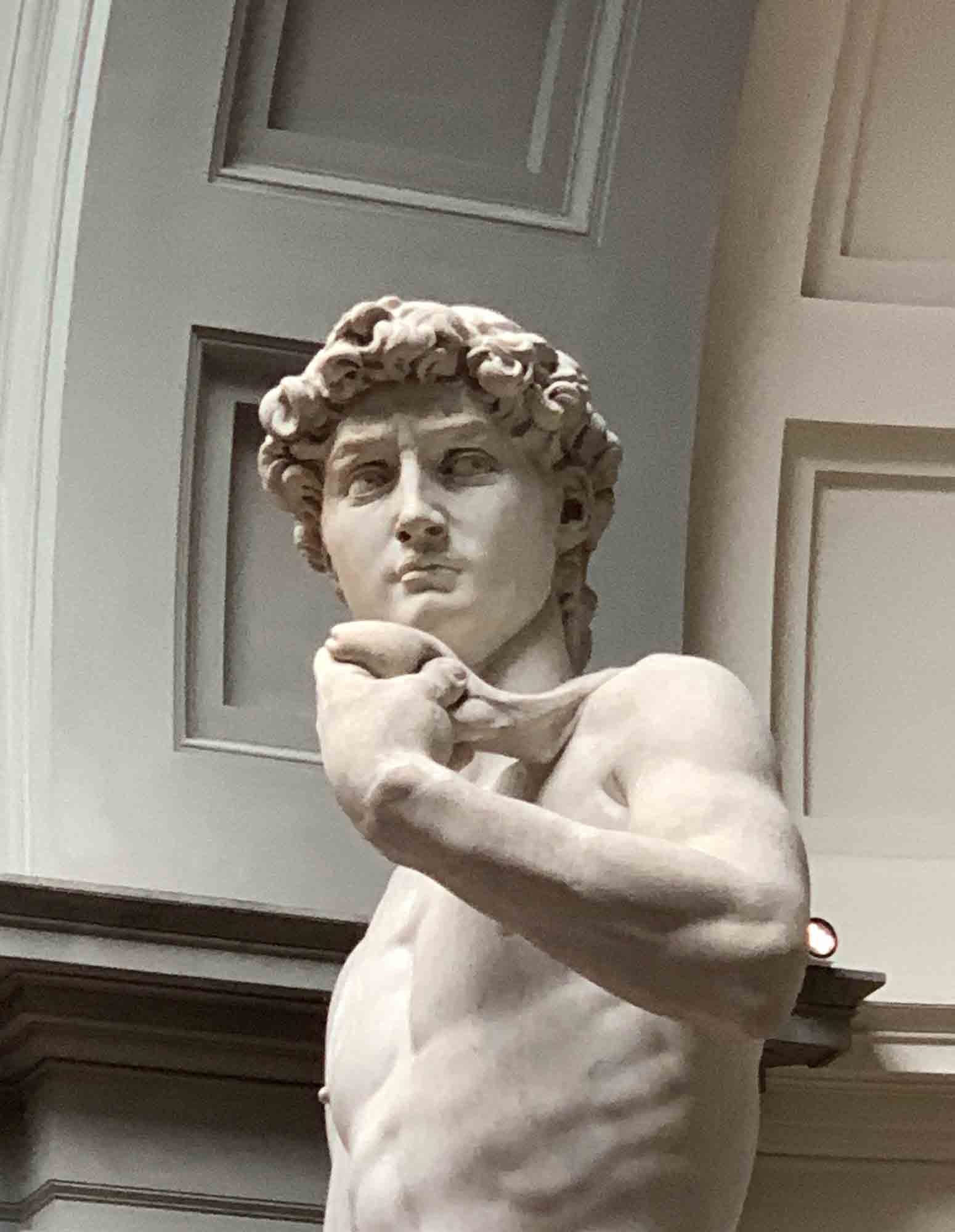

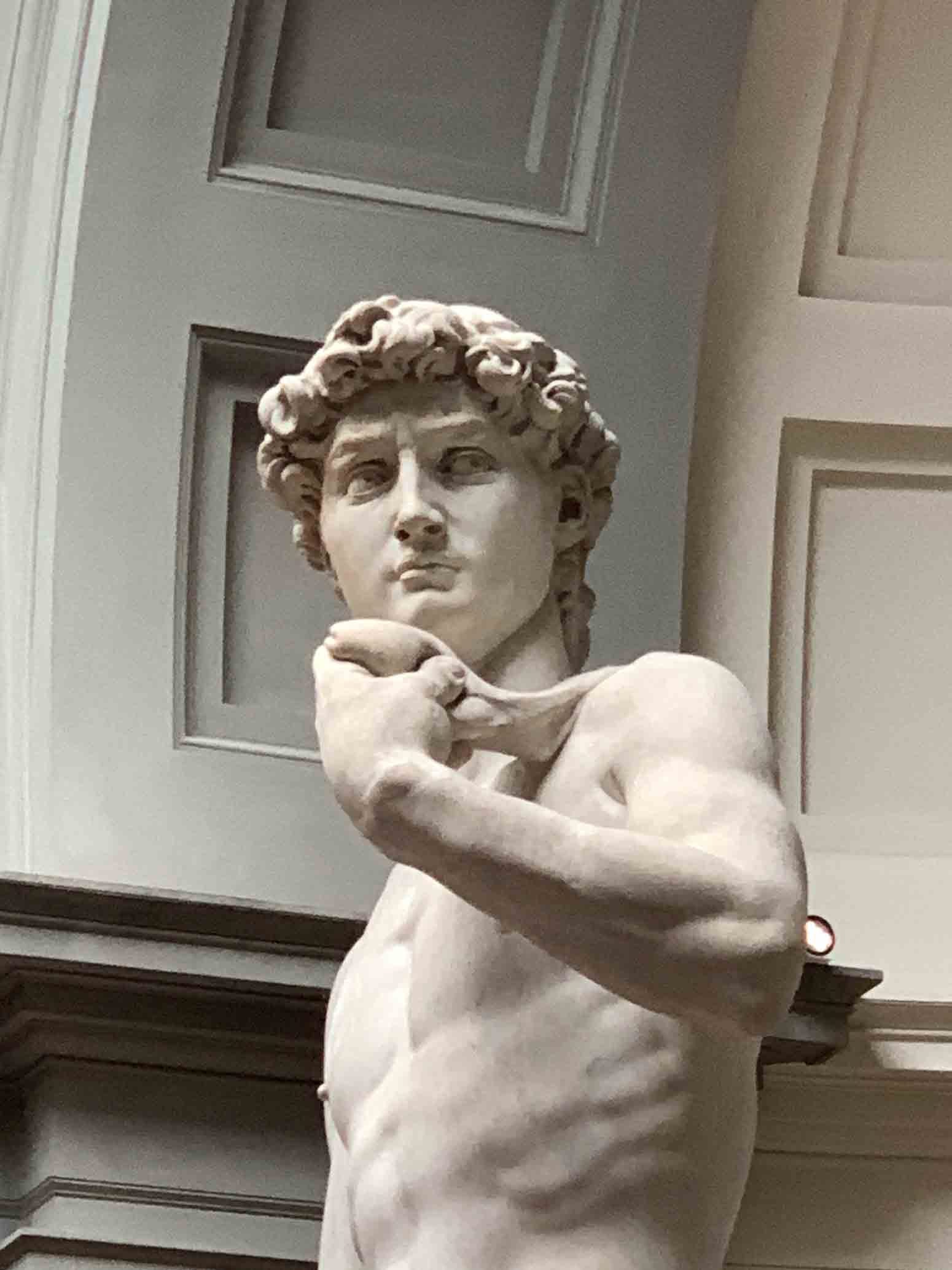

The second unsettling thing was the face. The David was, as I'd learned it, celebrated for its idealized musculature (musculature informed, Claudio said, by the sculptor's unlawful examinations of how cadavers were put together). But up above all that was the visage, compelling in a way that no static picture had even begun to convey.

Claudio had a whole protocol for dealing with the face, as he permitted us to approach the statue: starting with the most familiar angle, with the right side of the head toward the viewer, then making a quarter-circle counterclockwise to look straight at the face. From there—Goliath's point of view, he suggested—a new note of doubt or worry entered the previously confident expression. And so it did.

(Also, Claudio said, from this angle, Goliath couldn't get a good look at the sling.)

We worked our way around the statue, taking in the damage from the 1991 hammer attack on the left toes, the tricky veins in the structure of the marble at the rear, the carved anatomical veins standing out from the right hand and wrist. Everything was particular, precise, a direct expression from the mind and hands of someone working more than 500 years ago. There was no distance at all.

In the moment, it was hard to keep in mind that this was one constituent of something called the Renaissance, or that there were other immortal masters with their own immortal masterworks, or even that Michelangelo had done other things. As we moved on to the unfinished statues in the room, Claudio told a story—I have no idea if this is true, but it was the story he told—that Michelangelo had been so desperately eager to undertake a huge collection of sculptures for the pope's future tomb, he allowed the Vatican to extort him into a project in the field of painting, which he despised, and that was how he reluctantly took up his brush and got to work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. To which I vaguely thought, oh, yes, that was him, too, wasn't it?

Claudio showed us an unfinished Atlas in the hall, thighs and torso and a bent arm struggling out of a squared-off block of marble. Could we see the face? he asked. His iPad zoomed in on an image and he pointed it out—two rough notches and a perpendicular line, above the unrealized forearm, almost indistinguishable from the rough surface of the unworked stone, but clearly the brow of the Titan.

The tour was scheduled for one hour, which had seemed in the beginning like a bit much for a museum built around one artwork. At the end of the allotted time, Claudio gathered up everyone's radio sets and excused himself. We were on our own with the David, to work around it clockwise, maybe, or take some selfies with it, or just wonder at it. The exit went through the gift shop, as all exits do. There were Davids of all sizes there, full-length ones and busts. I had never felt less tempted to take home a memento of the museum experience. How could you hold onto something that was already eternal?

WEATHER REVIEWS

New York City, April 17, 2023

★★★ A plume of black smoke from a building's chimney pipe spread over the gray morning sky. A pigeon puffed itself up to the size of a crow. The garbage truck arrived with whoops and cries. It was a little too humid to wear the jacket and a little too chilly not to wear the jacket. A drizzle floated on the late morning air. A woman stood a rosy-cheeked child on top of a construction barricade for a view of a crew working down in a pit in the roadway. On Central Park West a man showed pale sockless feet in the loafers with his slacks and blazer; another man was out in a not-quite-matching ensemble of red shorts and red polo shirt. The drizzle left and the afternoon brightened until full sun shone on the front of the school, disorientingly free of its scaffolding for the first time all year. Blossoms leaned out over the park path from both sides. Tulips and dandelions alike were up. A golden retriever trotted by, head high, with a long stick in its jaws. The evening would have been perfect to be out in, if only there had been time to be out in it.

EASY LISTENING DEP’T.

The Indignity Morning Podcast is also available via the Apple and Spotify platforms.

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP’T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS for the assembly of select sandwiches from Brewster Book of Recipes, by the Woman’s Association of Brewster Congregational Church and their friends, published in 1921, found in the public domain and available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

PEANUT SANDWICH FILLINGS.

Grind peanuts; add chopped olives, a little catsup and Worcestershire sauce. Thin with salad dressing.

—Mrs. Morton.

Another method—Put peanuts through grinder; mix with mayonnaise.

TONGUE SANDWICHES.

Cold slices of tongue, dipped in mayonnaise and chopped fine. Parsley may be added. Dipping tongue in mayonnaise first seasons it better.

HOT SANDWICHES

CINNAMON SANDWICHES.

Make a paste of butter, sugar, cinnamon and spread on thin slices of hot toast.

—Margaret Ball.

CHICKEN FINGER SANDWICHES. Mince cold cooked chicken very fine; moisten with enough boiled salad dressing to roll in size of finger; season with minced celery and onion. Cover with thin baking powder biscuit crust, pinch ends together, brush with beaten egg. Bake in oven.

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, kindly send a picture to us at indignity@indignity.net.

Thanks for reading INDIGNITY, a general-interest publication for a discerning and self-selected audience. We depend on your support!