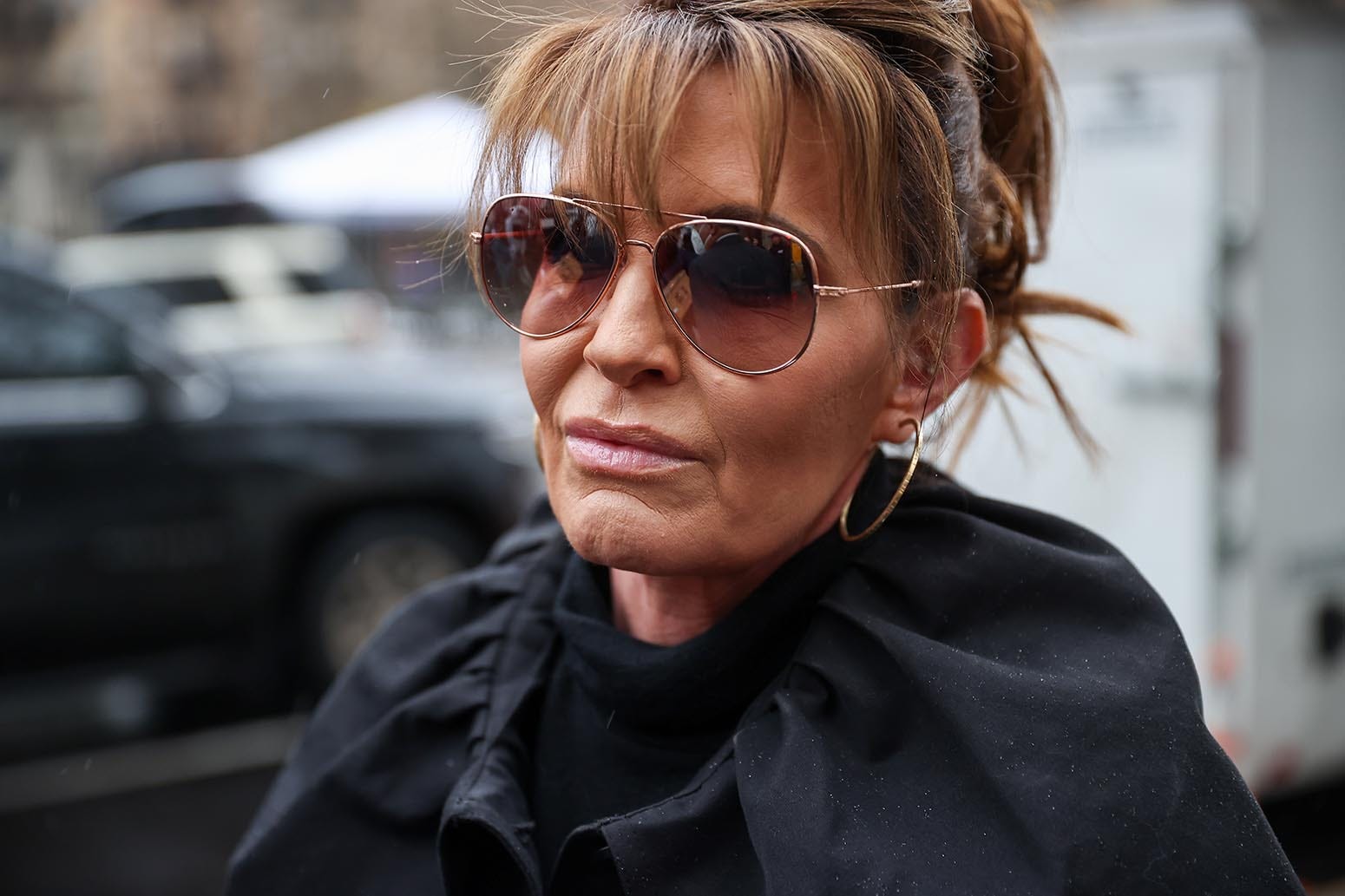

Indignity Vol. 2, No. 13: Palin lawsuit tossed, but not gone.

MEDIA STUDIES DEP'T.

Judge Clears New York Times of ‘Actual Malice,’ Keeps Jury Deliberating for ‘Inevitable Appeal’

WITH THE JURY still deliberating in the case of Sarah Palin v. New York Times, federal judge Jed Rakoff announced this afternoon that he would be throwing out the case. The Times had filed a motion arguing that, in the course of more than a week's worth of trial proceedings, Palin's legal team had failed to show that the newspaper had acted with the "actual malice" required for a public figure to win a libel suit. Rakoff, with some reluctance, agreed.

The judge said he disapproved of how former opinion editor James Bennet had inserted a false claim about Palin into an editorial about political violence in the United States. "I don't mean to be misunderstood," Rakoff said. "I think this is an example of very unfortunate editorializing on the part of the Times."

Nevertheless, he ruled that—under the "very high standard" set by the longstanding precedent of New York Times v. Sullivan—the trial testimony and the written record of the Times' internal discussions from the editorial-writing process had not established that Bennet or the newspaper were guilty of anything more than making a sloppy and thoughtless mistake in publishing the claim that "the link to political incitement was clear" when Jared Loughner shot Rep. Gabrielle Giffords in 2011, after Palin's political action committee had published a map with Giffords' district under crosshairs.

Although the Times' sometimes scattershot defense never quite articulated the point in the courtroom, one important feature of Bennet's error was that he hadn't invented the claim that Palin's map was linked to Giffords' shooting; instead, he had misremembered how that claim had originally played out. Bennet testified that he hadn't even perceived himself to be inserting a new factual claim into the draft he was editing, when he replaced a more vague reference to Palin and Giffords with the more sharply worded claim about "incitement."

From a layperson's point of view, it might have seemed strange or even damning that before inserting the untrue claim about the Palin map, Bennet had forwarded other editorial writers links to old news and opinion articles that correctly recounted its debunking. Palin's lawyers presented this as proof that anti-Palin bias had driven Bennet to recklessness, but journalistically, it sounded exactly like the sort of thing that can happen at a big institution when something is getting written by committee on a tight deadline.

Rakoff noted the apparent awkwardness of letting the Times off the hook for what he called an "ultimately unsupported and very serious allegation." The Sullivan standard is strongly protective of journalists' right to get things wrong—so much so that everyone involved expects Palin's lawyers to appeal the outcome, in the hopes of ultimately convincing the current Supreme Court, whose members have demonstrated hostility toward both precedent and the press, to weaken the protections.

And so, even as he said he would dismiss Palin's case, Rakoff said he was leaving the jury to keep deliberating until it reached a verdict. Given the "inevitable appeal," he said, he wanted a future appeals court to "have the benefit of my decision on the law and their decision on the facts."

"Needless to say," Rakoff said, "the plaintiff is deemed to have objected to my decision."

HAPPY VALENTINE'S DAY