Indignity Vol. 1, No. 20: The nice kind of calipers.

THE WORST THING WE READ THIS WEEK™

The Ladder of Human Ability Only Leads One Way

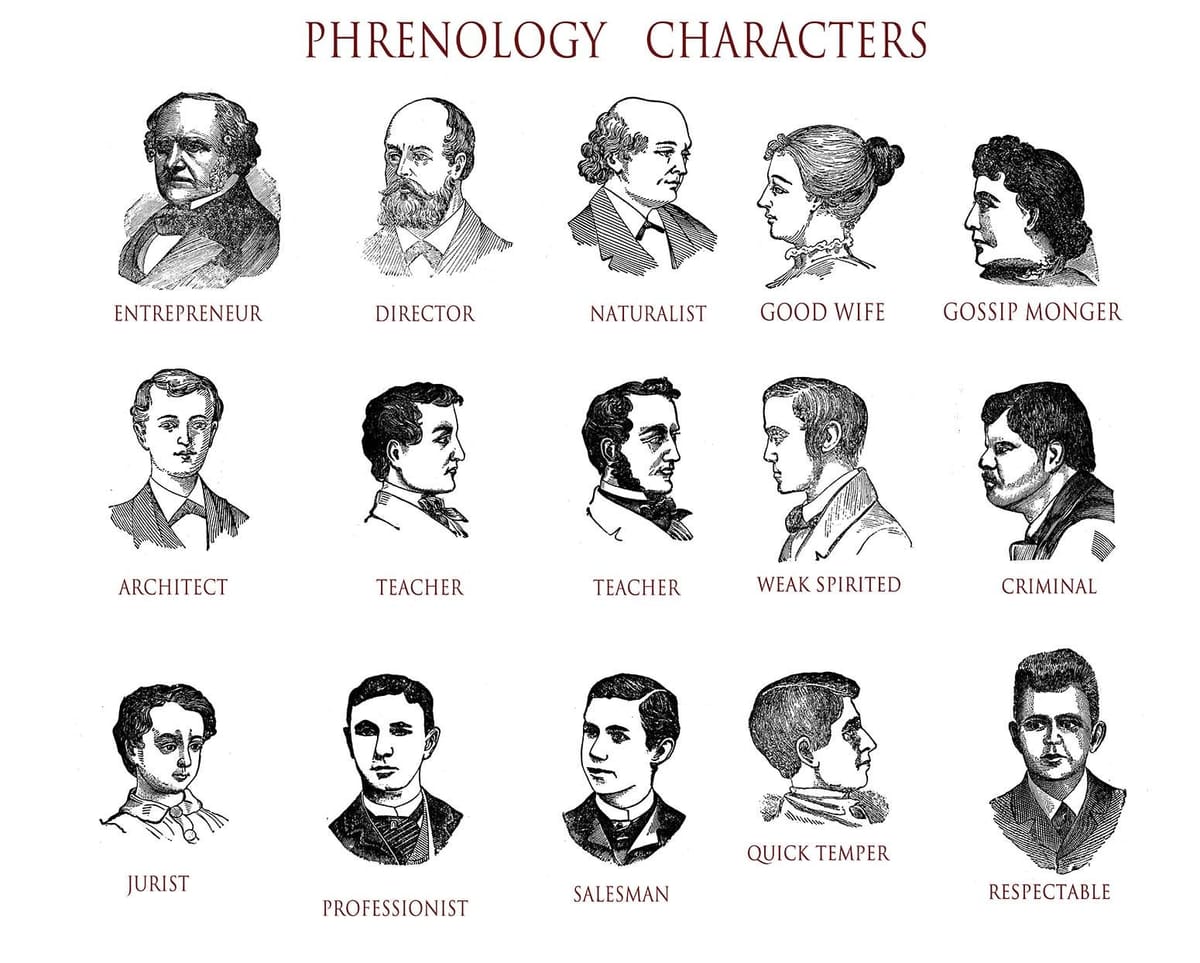

SOME PEOPLE ARE smarter than other people; everyone knows this. And some people are not as smart as they think they are. Where these two propositions meet, there you will find the phrenologists—laboring through the generations to prove the first point, and invariably proving the second.

The phrenologists don't like being called "phrenologists." Even the archaic ones would tell you they were doing "anthropometry" or "craniometry," and the modern ones prefer to call themselves things like "evolutionary psychologists" or "behavior geneticists." The latter was how Gideon Lewis-Kraus of the The New Yorker introduced his readers to Kathryn Paige Harden, profiled in advance of her new book, The Genetic Lottery: Why DNA Matters for Social Equality.

"Can Progressives Be Convinced That Genetics Matters?" the The New Yorker's headline asked. As with everything else in the phrenological sphere, the question started from its desired conclusion and worked backwards: genetics must matter, and progressives can either agree with this or be wrong. Harden studies genes—or rather, in a fairly important distinction, she studies data derived from the genome—and she wishes to be aligned with the progressives.

This is why she rated a New Yorker profile, because she is one of the Good Phrenologists, whose life's work is supposed to be knocking down the work of the Bad Phrenologists. She represents, Lewis-Kraus wrote, "an inchoate movement, sometimes referred to as the 'hereditarian left,' dedicated to the development of a new moral framework for talking about genetics."

Yet Harden, the profile explains, is criticized by the very people she says she agrees with politically. During a stint at the Russell Sage Foundation, Lewis-Kraus recounted, she was castigated by William Darity, "perhaps the country's leading scholar on the economics of racial inequality," who compared her work to "Holocaust denial research."

The reader was invited to join Harden in seeing this as an unreasonable—perhaps an irrational—attack. "Harden was surprised that she'd elicited such rancor from someone with whom she was otherwise in near-total political agreement," Lewis-Kraus wrote.

Harden is not a vulgar biological determinist or a genetic absolutist, and she emphasizes inborn individual difference over inborn group difference. She classifies genetic inequalities as only one of the many "arbitrary lotteries of birth," as Lewis-Kraus put it, and even within the genetic sphere, discusses "how gene-environment interactions can create feedback loops."

But Darity was perfectly correct. Whatever higher purposes an individual researcher may have in mind, there is only one question the phrenology business has ever sought to answer: Isn't it right that things are the way they are?

Over the past 50 years, the American phrenological project has particularly been trying to address the problem of ongoing racial inequality after the Civil Rights Era. Why are things still worse for Black people than for white people, even though the law has declared formal equality?

There are forceful and persuasive non-phrenological answers to that question—the result of generations of rhetorical, theoretical, and empirical work—that describe the material effects and the driving mechanisms of inherited inequity and ongoing racial discrimination. Racial injustice is a measurable and continuing phenomenon. Black Americans on average are born poorer, die sooner, and live harsher lives in between than white Americans do.

But the phrenologists are here to raise the possibility that, despite the evidence that these differences are laboriously manmade, the differences might really be natural. This was why Andrew Sullivan brought Charles Murray and Richard Herrnstein's The Bell Curve to the center-left readers of the New Republic—that is, to self-styled liberal Democrats exhausted by the long defeat of the Reagan years, looking to have the responsibility for justice lifted off their shoulders. What if it wasn't worth fighting for equality, because the races just weren't equal?

Harden isn't trying to say the races are unequal. She isn't even trying to say the races are races. But the racism of scientific racism is always stronger than the science. All the way back in the anthropometric days, the classifiers would open their books by declaring that all Man could be divided into three, or possibly five, distinct races, and before the end they would be awkwardly explaining that the people of this or that particular nation were characterized by an admixture of Caucasoid and Negroid features, overlaid upon the Asiatic type.

A century later, looking into the DNA, scientists have concluded that various different groups of people can be told apart, by ancestry, by their genomes—but that the social groupings called "races" correspond poorly, if at all, with such ancestry groups. As Harden herself wrote in a Vox piece on 2017, along with Eric Turkheimer and Richard E. Nisbett, explaining why Charles Murray's work is "junk science":

In reality, the racial groups used in the US—white, black, Hispanic, Asian—are such a poor proxy for underlying genetic ancestry that no self-respecting statistical geneticist would undertake a study based only on self-identified racial category as a proxy for genetic ancestry measured from DNA.

Yet even Harden and her coauthors couldn't keep this concept straight. In the same piece, they wrote:

Our lay concept of race is a social construct that has been laid on top of these vastly more complex biological realities. That is not to say that socially defined race is meaningless or useless. (Modern genomics can do a good job of determining where in Central Europe or Western Africa your ancestors resided.)

But "Central European" and "Western African" are not the same groups as "white" and "Black." The whole point is—or would be, if the well-meaning writers could have held onto it—that the prevailing social definition of race, in practice, depends on rejecting the idea that Central European ancestry meaningfully differs from Irish or Finnish ancestry. Social race doesn't care that some African ethnic groups are very tall and others are very short, or that you can carve up rural Britain genetically by county. All that matters is the color line.

And that is all there ever is to phrenology. No evidence can have the power to contradict it, let alone disprove it, because it insists on going where it's designed to go. The existence of genetic differences between populations, any populations—Basque, Dinka, Cornish—proves humans are not the same, which (with a quick wave of the hand) proves that the differences between Black and white people are ordained by nature.

Harden believes, and The New Yorker invited its readers to believe, that it's possible to make this landslide of motivated reasoning flow uphill. It's desirable, even. "The left's decision to withdraw from conversations about genetics and social outcomes leaves a vacuum that the right has gaily filled," Lewis-Kraus writes.

If liberals and leftists don't inquire into the natural-born basis of human inequality, then they'll leave the job of explaining why inequality is natural to the right-wingers. This is structurally and morally identical to the argument that liberals and leftists must embrace harsh anti-immigrant positions to prevent right-wing xenophobes from attacking immigrants; not surprisingly, the New York Times' studiously reasonable-branded conservative columnist Ross Douthat approves of both.

It is important to note here that Harden does not, in fact, study the question of how genes produce social outcomes. Frustrated by the slow progress of assigning clear social results to scientists' ever-more-complicated understanding of how genes operate, the behavior geneticists have simply skipped over the whole "how" business. Harden's work, Lewis-Kraus explained, relies on the use of the GWAS—genome-wide association study—in which computation is used "to identify hundreds or even thousands of places in the genome where differences in our DNA sequence could be correlated with a trait or an outcome."

"[E]ven if researchers don't fully understand what they're learning, this is how the genome is used now," an unnamed population geneticist told Lewis-Kraus.

Here's how Lewis-Kraus described Harden's own account of the tool she uses to address the most loaded social questions of our time:

GWAS simply provides a picture of how genes are correlated with success, or mental health, or criminality, for particular populations in a particular society at a particular time.....GWAS results are not "portable"; a study conducted on white Britons tells you little about people in Estonia or Nigeria.

That is, the genome makes people unequal, but it does so by an unclear mechanism, the effects of which are contingent on a person's social position in a particular time and place. Yet the reader was supposed to share Harden's regret or bafflement that Darity, a scholar of the material processes of racial inequality, would be hostile to her work.

Meanwhile, here was Harden, in an email to Lewis-Kraus, putting a precise number on the effects of visible discrimination:

Even if we eliminated all inequalities in educational outcomes between sexes, all inequalities by family socioeconomic status, all inequalities between different schools (which as you know are very confounded with inequalities by race), we've only eliminated a bit more than a quarter of the inequalities in educational outcomes.

Those numbers may sound low to those of us who attended underfunded public schools. Is three quarters of the difference in educational outcomes between my Aberdeen (Maryland) High School Class of '89 and the Phillips Andover Academy Class of '89 really due to our lower-quality germ plasm?

But Harden's message, the theory behind hereditarian leftism, is that there is no reason to believe that the effort to find inborn inequalities between people should lead to greater social inequality. Kraus-Lewis wrote, "Harden argues that an appreciation of the role of simple genetic luck—alongside all the other arbitrary lotteries of birth—will make us, as a society, more inclined to ensure that everyone has the opportunity to enjoy lives of dignity and comfort."

This is the disclaimer that Murray and Herrnstein attached to The Bell Curve, in a pose of political neutrality. If we decide we know that some people are naturally disadvantaged at school and in our education-based system of economic opportunity, who is to say that our society won't decide to help those people out more, to make up for it?

At least Murray and Herrnstein knew they were being cynical about this. Harden and her fellow hereditarian leftists seem to believe in phrenology as a neutral tool, an absurd position for self-styled empiricists to take. We have a long, detailed record of what happens when the skull calipers come out, and it's never an advance in equal treatment of all. As the UPenn professor Dorothy Roberts told Lewis-Kraus: "There's just no way that genetic testing is going to lead to a restructuring of society in a just way in the future—we have a hundred years of evidence for what happens when social outcomes are attributed to genetic differences, and it is always to stigmatize, control, and punish the people predicted to have socially devalued traits."

There's denialism going on here, but it's not, as Lewis-Kraus formulates it, that leftists "insist that genes really don't matter." It's that the phrenologists want to brush away all the hard-earned knowledge of how society works, and how racism operates within it. "Building a commitment to egalitarianism on our genetic uniformity is building a house on sand," Harden has written, in a phrase The New Yorker chose for the profile's epigraph. But building a hierarchy of human potential on our commitment to egalitarianism is building a house on molten lava.

No one disputes that mental and physical gifts are unevenly distributed. Some people are slow-witted from the moment they belatedly sit up or roll over in their cribs. Some people are brilliant while still in diapers. Many people are slow in some ways and fast in others, in a way that does or doesn't average out. Some people have bodies that grow to be six-foot-nine with extraordinary proprioception and savant-grade memory, and they have the chance to be LeBron James. Other people's bodies top out at six feet even and they only get to be Chris Paul.

All those people, with their various capabilities and potentials, are born into an unfair world. The question the neo-phrenologists are really incapable of answering about their chosen work isn't even "How?" It's "Why?" or, more bluntly, "Who gives a shit?" We know—objectively, factually, beyond the shadow of a doubt—that our educational system, like our society at large, is unequal. We know that poor children and nonwhite children are sent to worse schools. We know that they live under conditions of greater stress and deprivation, which interfere with learning. We know they receive less individualized attention, less support, and more hostility when they struggle.

Looking for genetic roots of academic and economic success, under these widely understood conditions, is perverse. It's as if, presented with widespread food shortages, one chooses to inquire into whether some people just metabolize food less efficiently than others. What's the point of trying to prove that some component of a person's ability to make the most of their learning might be genetically influenced, when we know that people are not being given the chance to make the most of their learning?

VISUAL CONSCIOUSNESS DEP’T.

The Car Show, part 2

More consciousness on Instagram.

REMINDER DEP’T.

THE SOPHIST is here to tell you why you're right. Send your questions to indignity@indignity.net, and get the answers you want.

SANDWICH RECIPE DEP’T.

WE PRESENT instructions for the assembly of sandwiches from Salads, Sandwiches and Chafing Dish Recipes, Copyright 1916, now in the public domain for the delectation of all, written by Marion Harris Neil, M.C.A., former Cookery Editor, The Ladies’ Home Journal, author of How to Cook in Casserole Dishes, Candies and Bonbons and How to Make Them, Canning, Preserving and Pickling, and The Something-Different Dish.

SARDINE AND ANCHOVY SANDWICHES

12 sardines

6 anchovies

4 ozs. (1/2 cup) butter

1 teaspoonful chopped parsley

Salt and paprika to taste

Buttered bread

Remove the skin and bones from the anchovies and sardines and pound them; add the butter, parsley, salt, and paprika, and mix well together; cut some thin white bread and butter it; spread freely with the sardine mixture, cover with a slice of buttered bread, trim off the crusts, and cut into fingers. Decorate with sprigs of parsley and serve on a sandwich tray.

If you decide to prepare and enjoy this sandwich, kindly send a picture to us at indignity@indignity.net.