Indignity Vol. 1 No. 12: The season of C-H-A-R-I-T-Y.

DISPOSSESSIONS DEP'T.

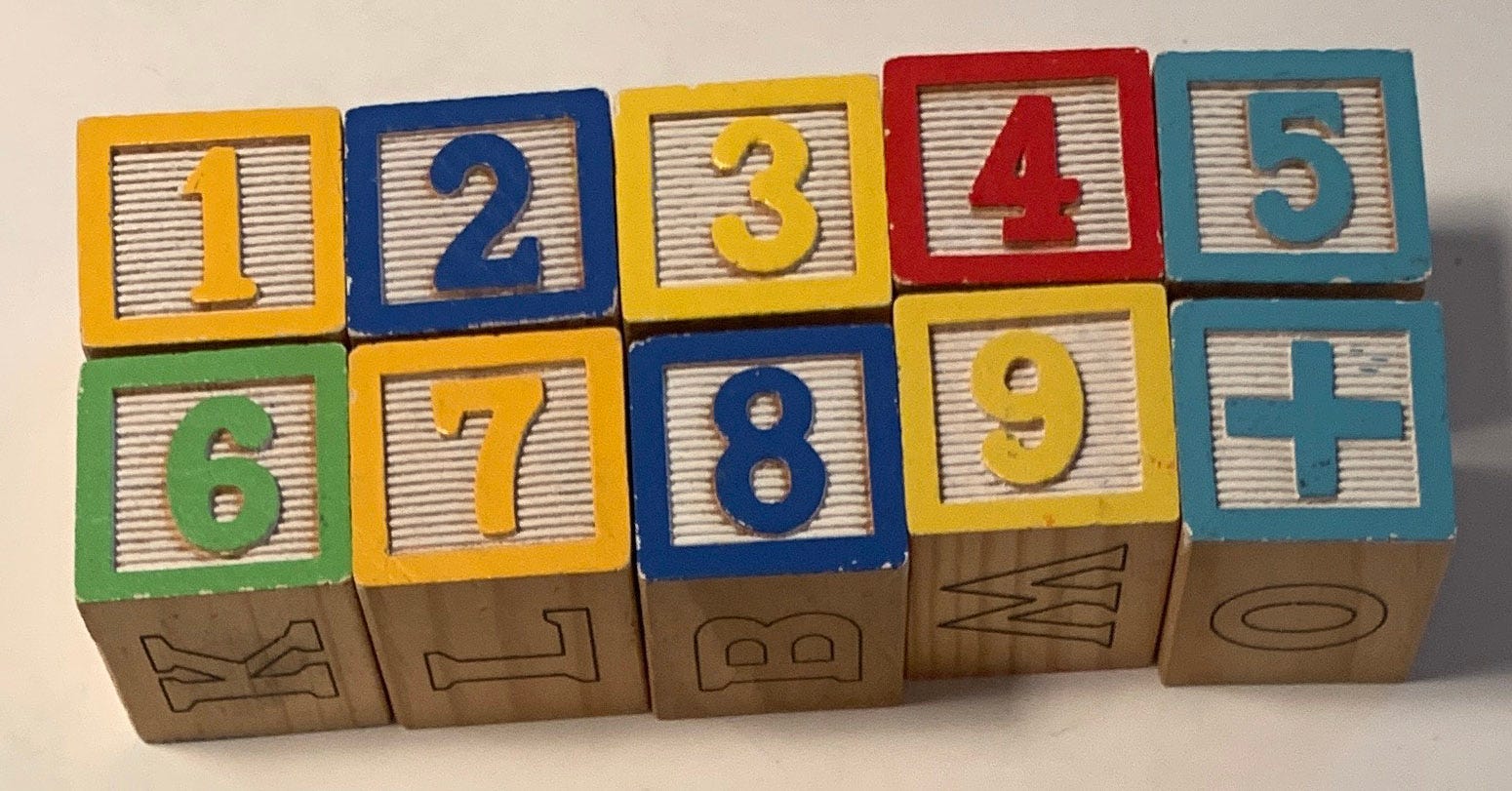

Wooden Alphabet Blocks

I NEVER THOUGHT about how Christmas would work in the children's hospital until we were spending Christmas in the children's hospital. Even then, at first, the Christmas question didn't seem relevant. Few things having to do with time, or with any other external points of reference, did.

Time had started falling apart at the pediatrician's office, where we'd taken the child, a year and a half old then, to get his fever and cough looked at. My wife and I had never seen these pediatricians before; we'd only just moved back to the United States after living in China, and the child had gotten sick during the 13 1/2 hour flight. We had no car because we were living right by the Silver Spring Metro stop, in an apartment we'd rented sight unseen, so for this, once we figured out where the doctor's office was, we called a cab. We thought we'd get the child checked and then call another cab and go home.

He's fine now. He's a hungry and growing teenager. This isn't one of those stories.

But: instead of letting us go back out into the afternoon, the pediatrician checked his oxygen levels and started giving him breathing treatments right there in the office. Then, as the afternoon sank into evening and they kept checking his oxygen, they called an ambulance. The ambulance took us all to the hospital—only one parent was supposed to ride inside, but we told them that we had no car, and they bent the rule—and the hospital gave him another round of treatments, as episodes of Dora the Explorer played one after another on the TV in the corner. While all of this was going on, I perceived myself as reacting calmly in face of the crisis, but for years afterward I would feel trapped and panicky every time I heard the Dora theme.

Somehow, at some later hour of the night, the hospital conveyed to us that whatever they (the hospital!) were doing for the child wasn't exactly working, or it was not working well enough, or it was not working as well as the treatment he could be getting from the experts at the children's hospital, which was, they conveyed to us, where we should really go. Now. By this point my mother had shown up from an hour and a quarter away, with her car, and the ambulance went on ahead of us in the dark while my mother and I briefly stopped off at a supermarket—incomprehensibly immense and gleaming, simultaneously overfilled and spacious, after my time in China—to try to find something to bring along for people to eat, somewhere, in lieu of long-past dinner.

I can't recall what food we bought, or how we ate it, or really much of anything else, not in any structured narrative. After the grocery store, everything blurred into the round-the-clock sameness of the children's hospital. We got to a room; the child got festooned with various wires and tubes and adhesive tape and a glowing pulse oximeter; nurses and doctors appeared and did things and went away. At some point the word "pneumonia" came up, though it may have been speculation. It was a name we could use for the situation, at least.

Beyond that, the situation was stubbornly shapeless. Days passed, and also hours, and minutes. One or the other of us lay in the hospital bed with the child, tilted on an incline. We were all still fully jet-lagged, with that opposite-side-of-the-world jet lag that brings on late-night chills and confusion in the middle of the afternoon. The pulse oximeter, I do remember, was set to sound an alarm if its blood oxygen measurement dipped below a certain level—95, or 96, or something—and the reading dipped below that level all the time, over and over, just long enough to trip the alarm and wake everyone up, before it would immediately return to the safe zone. I hated that oximeter, not just because it made it so that no one could get even a decent nap's worth of sleep, let alone a good night's rest, but because it kept signaling that there was an emergency when there was no real emergency. It was gratifying to hate it for that.

Otherwise—there's an absolute gap in my photo library at the end of that year, and a near-complete gap in my email archive. Memory doesn't do much to fill in the blanks. There was one time, I know, when I was starving and I got a restorative serving of stewed greens from the hospital cafeteria. There was the night a sleet storm hit and I was on the cell phone from the child's hospital bed talking to my wife as she waited in the wet, icy wind for a bus that wouldn't come. I couldn't leave the child and come get her, and by the time she did make it home she was so frozen and battered she came out wracked by a chest infection of her own.

But then one of the days arrived and that day was Christmas. Probably there were decorations? What I know for sure is that someone came and got me and I was brought downstairs to pick out some free Christmas gifts for my hospitalized child. They had a room with shelves of presents, sorted into different categories, and a kind of inventory sheet listing how many of each type you could take for your child, depending on age. I wasn't going to take the full allotment, of course. We didn't need a hospital Christmas, really. We just happened to be in the hospital on December 25.

Still, it was worth putting in the effort to participate. Right? My eyes fell on a small stuffed pig (the child and I were both born in the Year of the Pig) and I couldn't stop looking at it. It was rather skinny and alert-looking, for a pig, but also oddly lifelike, with an almost pointy face and something plaintive yet trusting in its expression. And very, very soft to the touch. He should have the pig. There were books, too. I picked out a slim little paperback classic—Harold's ABC, I'm pretty sure, though it might have been Harold and the Purple Crayon.

And then—OK, one more thing—I hunted around the shelves until I found a set of wooden alphabet blocks. The child loved letters and numbers. These were carved and painted on two sides, and printed on the other four, and they came with a cloth carrying sack. The whole set had the character of something old-fashioned and enduring, a fixture of a normal childhood, the sort of thing that would be around the house for years.

That was enough. Nearby they were serving cookies and hot beverages for the parents or the kids who could make it downstairs. Volunteers were wrapping the gifts—beneficent teen volunteers, sacrificing part of their own holiday to bring a little cheer to the misfortunate. And also to us, which was honestly a little embarrassing. We were fine, really fine, just passing through. They might even have sung some carols?

Back upstairs, to complete the whole process, a Santa came around the ward. It seems to me as if they must have snapped photos, but the child wasn't cut out for Santa interactions even when he was at his best. I gave him the pig and read to him from the book. I'm pretty sure I'd skipped the giftwrap, since the child was still a little young for unwrapping things. It wasn't really feasible to play with the blocks until after we got out.

And we did. We got out. We all went home. It took two more days. It might have taken less but the child's circadian rhythms were still upside down, so he'd be logy when the doctors checked him during the day and perky at 4 a.m. There were still nine whole days of Christmas left. We must have gone to see my parents for a more proper celebration, but I have no recollection or pictures. My photo roll resumes a week into January, with a shot of the child in his brown puffy coat, up and about for his first day of preschool in America.

The stuffed pig became his boon companion, No. 1 or 1A among all the stuffed animals. The Harold book took a place in the cycle for storytime. The alphabet blocks were just OK. As building blocks, they never could compete with the bigger sturdy German hardwood blocks from the Lufthansa shopping center in Beijing. When he really wanted to play around with letters and numbers, he got on an old laptop and started messing around in Word. He did discover that he could use the blocks to deboss backwards numbers and letters into Play-Doh, which dried out into little squarish chips he left everywhere.

Mostly, the blocks stayed in their cloth storage bag in a filing cabinet drawer taken over by toys. His little brother wasn't particularly interested in them, either. Finally, after several apartments and nearly a dozen years, we needed the drawer space for something else. The blocks had done everything they were going to do.

REMINDER DEP’T.

THE SOPHIST is here to tell you why you're right. Send your questions to indignity@indignity.net, and get the answers you want.

VISUAL CONSCIOUSNESS DEP’T.

Making a Raisin Sandwich

More consciousness on Instagram.

THOUGHT DEP’T.

Do you have a thought? Send it to indignity@indignity.net.