HOW DID YOU SLEEP LAST NIGHT?

A collection of the ongoing series by Lori Teresa Yearwood.

January 5, 2021

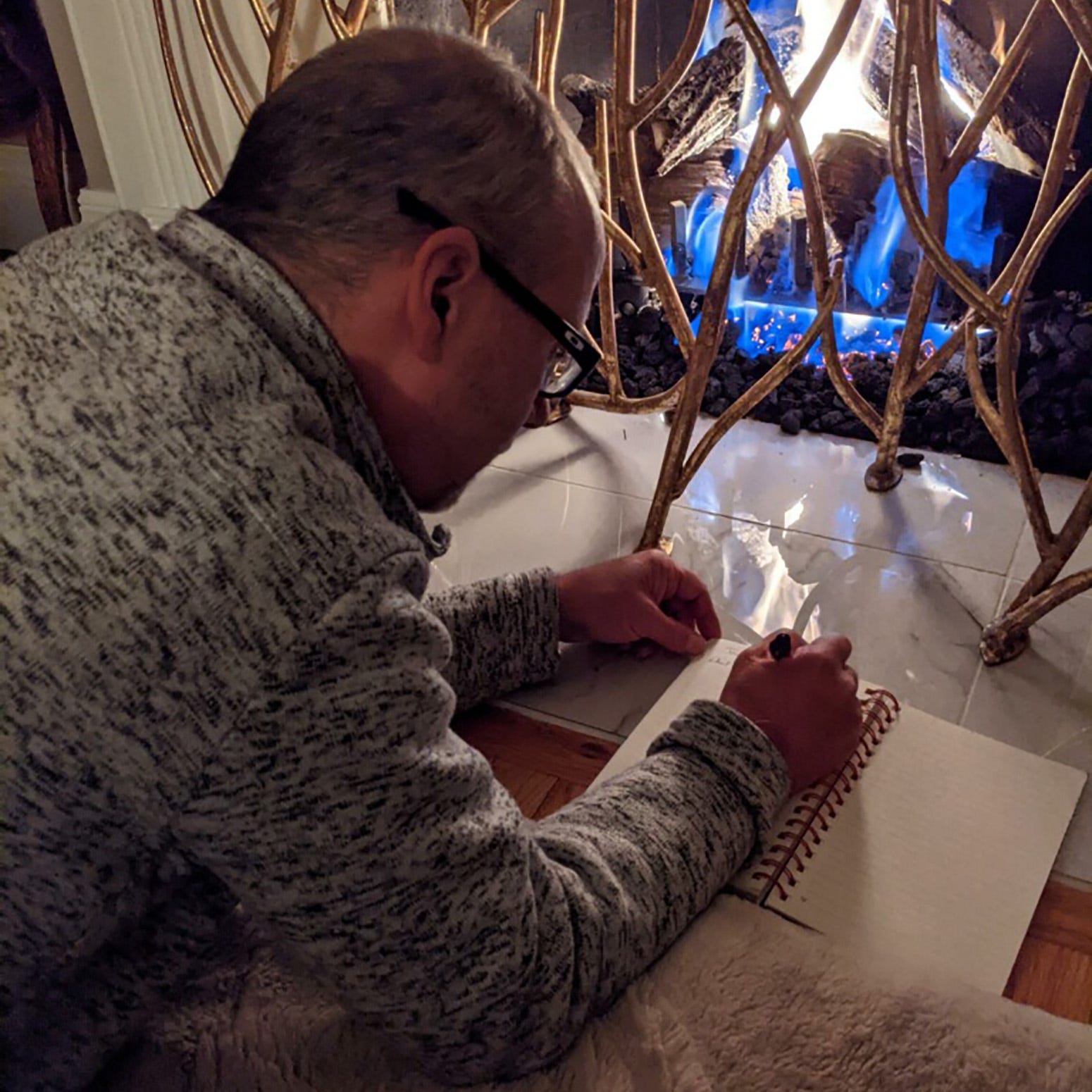

Mike Sheffield, Utah

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

FOR DECADES, Salt Lake City psychologist Mike Sheffield has had a complicated relationship with sleep.

“It’s hard for me to turn off my mind,” he said. “I struggle to slow my mind down.”

It started with chronic fatigue syndrome nearly 25 years ago. When that condition improved, the sleeplessness nevertheless came back with a cancer diagnosis in 2010 and lasted through two years of worry about whether he was going to live or die, Sheffield said. Even when his long-term survival became more evident, Sheffield, now 56, said nights of uninterrupted sleep have not become a regular reality again.

No matter what he focuses on—his home remodeling project gone awry, or the state of this country’s politics— “I have a hard time sleeping through the night,” Sheffield said.

He struggles with the decision to take sleep medication, going through times when he takes it and periods when he doesn’t. Complicating the situation is the fact that Sheffield was diagnosed with sleep apnea several years ago, and so breathes with the help of a CPAP machine.

Yet there is always something Sheffield looks forward to each night: the meaning and sometimes even guidance that he’s learned to garner from his dreams. Thus, a red notebook remains on the nightstand by his bed. When the dreams do come, Sheffield wants to be ready to jot down the details and ponder them later on.

“I have made major decisions in my life because of my dreams,” he told me.

Countless dreams have proved to be extremely useful in his daily existence and personal growth, he says. In fact, two of them forever changed his life, he says.

The first one came in 2005, when Sheffield said that he was wanting to leave his full-time job to work on his own, but did not feel he had the financial means to make that leap.

“I am staying at a condo complex," he said—when he talks about these dreams, no matter how much time has elapsed, he still uses the present tense—"and I follow this guy to a cliff overlooking the water where there are huge waves crashing across the rocks. It’s called ‘The Tides of Ruin’ and the guy—without hesitation—dives in.

“I knew it meant certain death. But I was connected with him and I have to follow. So he dives in and once I’m in the water too, he just disappears. I’m just by myself, swimming deep under the water.

“I know if I stay deep, I’ll be OK. And I know if I get to the surface, I’ll be smashed and die. So I’m swimming and I see a serpent below me, and right as I reach the shore, the serpent burns up completely and the bones fall to the ocean floor and I die at the same time, just as I’m reaching the shore.”

Suddenly the scene changed: he was back in his condo with his friends, and the man who jumped in the water—Sheffield has since dubbed him The Leaper—walked in. This time, the Leaper’s heart was visible inside his body.

“When I woke up, my first thought was: ‘I have to take the leap, even though it feels like I will be ruined,” Sheffield said. “I know I’m going to have to swim deep and not near the surface, where I would be completely battered by fear and turbulence.”

Concluding that the characters had represented parts of himself, Sheffield decided to take the dive. He took out a substantial home equity loan. He started doing psychological testing on his own. He also immersed himself in writing songs, poetry, and autobiography. And he tried to start a business offering personal workshops in the wilderness.

“And for various reasons, none of those things panned out,” Sheffield said. Yet the entire time all that was happening—even when he thought his financial situation might force him to sell his home—Sheffield remembered that dream, reassuring himself that he was traveling through a deep, albeit inscrutable process.

“I believe that dreams can give access to the steps of the psyche, as well as all the energy of the psyche, and so you can experience all of who you are in dreams,” Sheffield said.”You can open up to something deeper that wants to come through.”

Back in reality, the woman with whom he was having a relationship offered to rent Sheffield’s home. Intending to eventually live in his truck, Sheffield accepted her proposition and moved—temporarily, he thought—into a room into the basement of the house. Six weeks later, he was diagnosed with breast cancer.

His then-girlfriend vowed to remain by his side and Sheffield found himself navigating a terrifying terrain upon which he needed to decide whether to have a single or double mastectomy. The oncologist he was working with at the time said that when it came to situations like Sheffield’s, particularly those involving men, the suggestion was generally to remove only one breast.

Still uncertain as to what to do, Sheffield had another dream: “I meet these two girls and somehow I know that one has one breast and the other has zero breasts...We’re all going to this parade and the one with one breast kind of wanders off, talking to other people. And the one with no breasts stays close by me and keeps talking to me and we are developing more and more of a connection in the dream."

With a profound feeling of peace, Sheffield went ahead with the double mastectomy.

Though the terror of a cancer recurrence stole many nights’ sleep, the psychologist’s relationship with his dreams, and thus with himself, saw him through the fear. As he had with the dream about The Leaper, he said, he referred to the notes about the dream in the journal to help him.

“I got panicked every day for two years,” Sheffield said. “Sometimes it would last for 10 minutes and sometimes it would rage for hours. And I just, I just kept going.”

It turns out that Sheffield never left that house he thought he would have to sell. He and his wife —the same woman who rented his home and saw him through the cancer—still live there. Even the clarity to marry her made itself evident in a dream, Sheffield said. His finances have improved dramatically since then. And in hindsight, he can see how things worked out for him while he followed his commitment to “dive deep” into uncertain waters, he said. Doing all that inner work changed him, preparing him in unexpected ways to navigate what was to come.

Of course new dreams continue to come. But sometimes, because of his inability to sleep, Sheffield is hesitant to focus on writing them down. He worries that the writing will more fully wake him up, and cause him to lose precious sleep.

Still, he wills himself to push through the jostled nights of fitful sleep to use the red notebook. Without that effort, he knows, the memories of his dreams will fade away unnoticed.

“I have this commitment to try to make something beautiful out of what happens to me," Sheffield said. "And dreams help me do that.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

Dec. 22, 2020

Michael Anatole, New York

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

A YEAR AGO on Christmas Day, Michael Anatole attempted to sleep in a homeless shelter in downtown Manhattan. It was a room filled with 70-some men in a space that stank of unwashed clothes and body odor, and it constantly erupted with the cacophonic tumult of street life crammed inside one dimly lit dormitory-style room.

Sleep came. But only enough to survive, Anatole said.

“There is sleep that just allows you to continue breathing as a human,” he told me, his voice filled with the resolve that carried him through those long nights and tired days. “And there is the sleep that is restorative.”

“Every night was a bad night there,” Anatole said. “I hardly got more than four hours of sleep every day.”

This year, though, is drastically different. Anatole—who worked full-time the entire seven months he was homeless—has thrust himself into the stratosphere of the housed. In this much more mundane realm, the 56-year-old Anatole has his own bedroom in a shared, three-bedroom apartment that he has been renting with two other working men since June

Every night, starting at around 9, Anatole prepares himself for sleep by engaging in the most ordinary of human rituals, the types of activities that he so desperately missed when he was homeless.

He puts a scoop of vanilla or strawberry ice cream in a white ceramic dish he bought at a local dollar store. He carries his treat into his bedroom. He shuts the door. It’s a hugely important moment, the shutting of that door.

“Being able to close my door and not have anyone else inside my environment other than me—that is peace,” Anatole told me.

Then he sits on the edge of his bed and eats his ice cream. Slowly, savoring its cold sweetness.

“No TV, no music. And all is right with the world because I am enjoying my ice cream alone,” he said.

A few times a week he replaces the ice-cream with caffeinated coffee, which, believe it or not, he said, helps to clear his lungs but does nothing to hamper his ability to sleep.

“It’s just plain espresso coffee that I make in a stovetop maker that percolates,” Anatole said. “Sometimes I drink that. I really enjoy it.”

This carefully cultivated peacefulness is supported by considerate housemates, one of whom is the owner of the sixth floor co-op apartment that adheres to rules that keep the noise on 145th Street in Harlem outside the building's brick confines. The other housemate is a successful food-deliverer who sometimes doesn’t make it home until 11 p.m. but is careful to walk quietly and directly through the apartment and into his own bedroom.

By that time, Anatole has taken his medication for the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease that has put him in intensive care twice this year alone, he said. He’s also likely watched Jeopardy! or The Big Bang Theory on television, or read. He’s read Shakespeare repeatedly; “the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” he sometimes said when referring to his tough times.

These days sleep comes in uninterrupted blocks of six, seven, even eight hours at a time.

“My sleep is a hell of a lot better now,” Anatole said with a laugh. Suddenly, we shared a mutual acknowledgement of the incredible superpowers that it took for him to make it through that time in his life, and we laughed together.

“I also do believe that if you aren’t looking to get out of that situation as soon as possible,” Anatole said, “you mentally start to degrade and your social skills start to erode. Your analytic skills also decline.”

Research on sleeplessness bears witness to Anatole’s statements, showing that sleep deficiency is an important risk factor for a wide range of adverse health outcomes, including high risks of cardiometabolic diseases, mental disorders, cancer and mortality in general. But even without such drastic consequences, the ramifications of sleep deprivation can make it impossible for someone to regulate emotions and successfully navigate life, still more studies reveal.

Still, Anatole held onto his job gathering essential data for the city’s computer systems. Born and raised in New York, he graduated from Pace University in 1985 with a bachelor’s degree in management information systems, he said.

He makes $45,000 a year in his current position, a job he’s held for six years, he said.

“I kept telling myself, ‘You’re going to get out of here, you’re going to get out of here—this is not something that is going to be permanent for you,” Anatole said about his time in homelessness.

Though he said he doesn’t want to go into the personal details about what sparked his fall into the life of the unhoused, he did say that he was depressed and that the depression played into a spate of absenteeism from work, causing loss of pay. His then-landlord locked him out of the room he was renting because Anatole owned approximately $1,000 in back rent.

At first, Anatole lived in the noisy day-to-day shelter that smelled constantly of funk. Then, in January, he was accepted into a program at the New York Bowery Mission where he paid 20 percent of his income to stay at the shelter. That place was a palace compared to the first shelter, Anatole said. But it was an environment that was far from conducive to sleep.

“There were definitely noises in your environment that were not of your own,” he said. “People getting up in the night. You could hear wrappers opening up and soda cans popping open.”

There was one man, who every night after lights-out at 10, “decided to clean the bathroom from top to bottom—every shower, every toilet. Everything he had, he decided had to be scrubbed with as much bleach as he could possibly find—to the point where the entire dorm room would stink of bleach.”

When the man wasn’t cleaning, he was rearranging the plastic bins in which he stored his life.

“He had one of those halogen high-beam flashlights. He would hang it up by his bunk and flash it,” Anatole said.

In those months of shelter sleep, Anatole felt like he was thinking through a kind of fog. He also remembers that he felt a propensity toward anger that he hadn’t felt when he was well rested.

“You don’t feel sharp and you don’t feel present in your interactions,” Anatole said. “On any given day, your mind just wanders and drifts—and you may not even be conscious you’re doing it.”

Despite it all, Anatole saved every cent he could—he eventually stashed away five thousand dollars, he said—to move in June into the apartment where he lives now. Given the costs of renting in New York City -- the average cost of a studio rental there is $1,889 per month, according to a 2019 article from Smart Asset.

Anatole got lucky and found his home for $975 a month on Craigslist. In the past two months, he’s felt so secure, Anatole said he hasn’t even had to take melatonin to fall asleep.

“My life is about being normal now,” Anatole said. “I find that peaceful. My problems are like everyone else’s problems. I find that a comfort.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

Dec. 8, 2020

Betty Long, Utah

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

TO FALL ASLEEP, Betty Long knows that she must first relax. Problem is, when COVID-19 hit this country in March, the 47-year-old lost her job as a food and beverage manager of an upscale Salt Lake City hotel, and despite applying for countless jobs, she hasn’t worked since.

“I’m always thinking, what’s my next move?” Long said. “Do I stay in the industry? Or do I start over and do something else? This is what I contemplate at night.”

Long, who was making $54,000 a year and living in a gated apartment complex, has been receiving less than half that amount in unemployment benefits. In April, she moved into a three-bedroom apartment with family members who have also been financially set back by COVID.

Every day, she watches the news to see if the restaurants that she might be able to work in are still open.

“Suddenly your job is based on the news of, is your city open?" she said. "Can people travel to your city? Everything has completely changed.”

Every night, to drown out the news of what she can’t control, Long turns up the noise on the devices she wants to see and listen to: her television, her phone, her computer, even her bedroom light.

“It’s hard to sleep because it’s a helpless feeling,” Long said.

During the first six weeks of the coronavirus pandemic in the US, 5.9 million workers in the restaurant industry lost their jobs, the industry publication Restaurant Business reported. That made the industry the hardest hit by unemployment, according to Forbes.

Meanwhile, according to Utah’s coronavirus dashboard, Utah County, which is where Long lives, has a seven-day rolling average positivity rate of more than 31 percent.

“It’s not like you can move to another state or even country,” Long said. “All the restaurants are either closing or barely staying open. A lot of chefs I know have lost their jobs as well.”

Long earned her associate’s degree in 2015 in culinary arts from Salt Lake Community College while raising her daughter, Zala, as a single mother. She described the current job-hunting scene as “cutthroat,” because it feels as if “everyone is suddenly and collectively” applying for a job, she said.

When she’s made it past the online application process and into the job interviews, Long said, she is usually told that the position isn’t actually what it was billed to be.

“The job says general manager, but they want you to manage and cook and bartend—on top of everything else because there is less money out there,” Long said. “I’m like ‘That’s not what the agreement was.’ ”

Still, her experience in the field gives her an open-minded perspective. “You’re talking about restrictions forcing restaurants to go from 100 percent open to 25 percent open,” Long said. “How can they keep staff with that? Everyone in the food industry got hit at the same time.”

In the end, the advertised job titles haven’t mattered, as Long said she hasn’t been offered any jobs yet. Thus, Long, a chef who specializes in cooking for hundreds, if not thousands, at a time, has expanded her job search to the realm of the fast food industry. But those fields are clogged with applicants, too.

“They keep telling me I’m overqualified,” Long told me.

Long once oversaw food operations in a Utah prison, and said she'd thought about working in one again, though prisons are known hotspots for COVID transmission.

“But then I realize that I would be putting my life at risk, as well the lives of those I live with,” she said. “And I ask myself, is it worth it?”

As far as she knows, Long’s unemployment benefits—which come to less than $2000 a month before taxes—ended on Tuesday. Congress has been debating a second stimulus package for months, with no result.

Long is having a difficult time unwinding, as normal activities have fallen by the wayside, including karaoke and hanging out in person with friends. She still takes walks, but even that activity has taken on an additional stress, as so many more people are also outdoors these days, she says. And while she wears a mask, not everyone else does.

“Relaxing is a totally different situation that it used to be,” Long said. “I don’t relax as easily during the day as I used to. And that’s what I need to be able to fall asleep more easily at night. So I never feel fully rested.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

Nov. 24, 2020

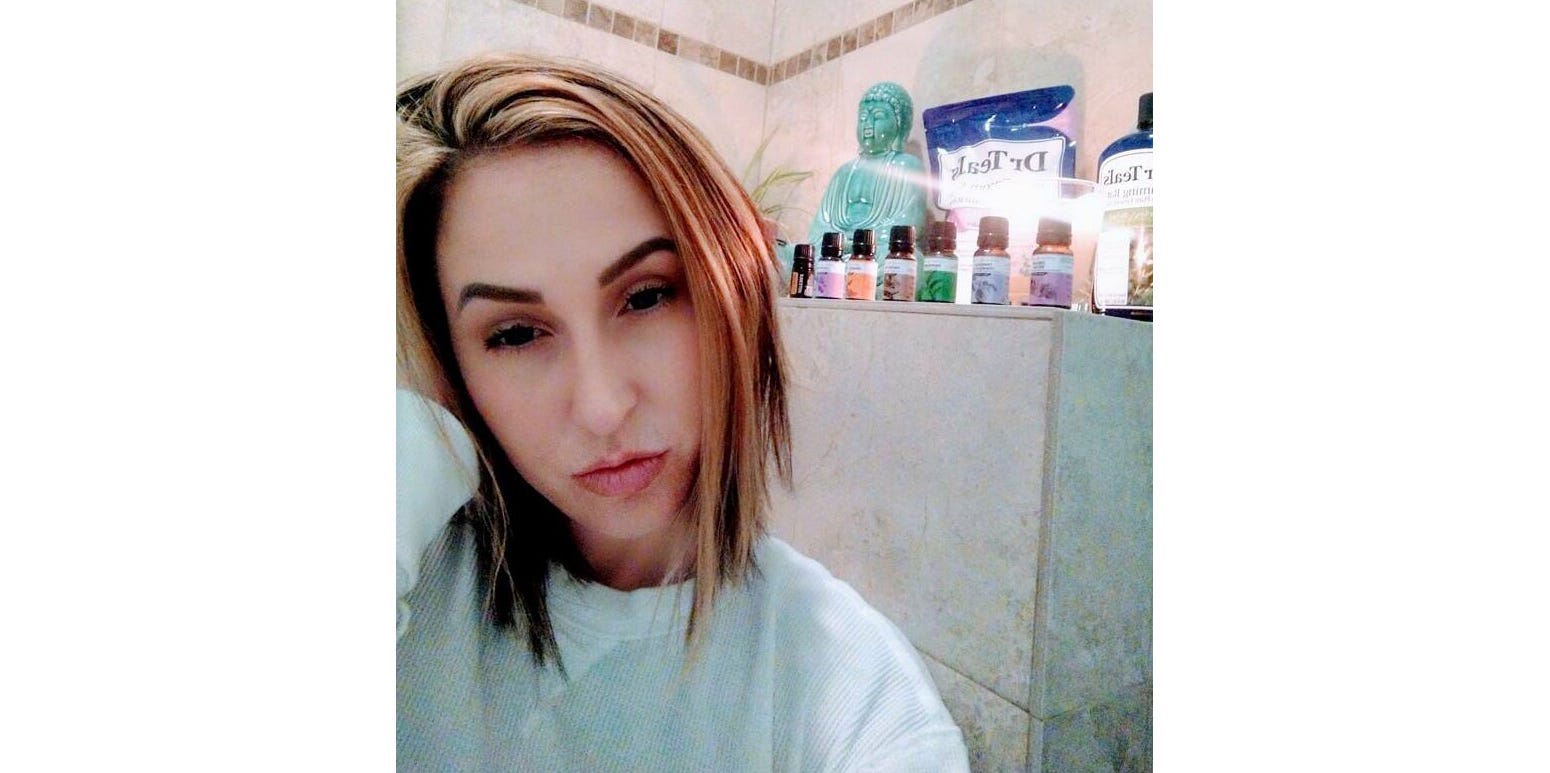

Amber Kehl, Utah

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

AMBER KEHL’S NIGHTMARES are usually about the man who sex-trafficked her, “the one who really, really hurt me—physically, sexually, emotionally and spiritually,” the Salt Lake City resident said. She spoke so quietly that it was as if she were still in one of the dreams, reporting on it from the inside out.

Last night was particularly horrifying, she told me on Sunday.

The nightmare started in a hallway. Suddenly, the scene changed and the 36-year-old found herself in an elevator, something she avoids in real life, as elevators remind her of feeling helpless and trapped. “But in the dream I didn’t have any options but to use it and when the door opened he was there,” Kehl said.

The man didn’t recognize her at first. “I was wearing my [COVID] mask in the dream. But then there was eye contact and he slowly realized who I was, and then there was another level of intense fear. And I felt like I was being hurt in the dream. I remembered the feeling of it, not the images of it.”

The dreams focus on some “wild, chance encounter,” Kehl said. When she wakes up, her body twitches “and I lay there shaking. And then I try to be quiet again.” The most she’s slept in any given night during the last four years has been four hours of solid sleep, she estimated.

“I keep my eyes closed, I don’t move my body. I hold still and tell myself: ‘Just keep your eyes closed,’” Kehl said.

It’s a nightly ritual that Kehl said she is working to unlearn. It’s difficult to let go of, because feigning sleep is something she did to protect herself when she lived within the grip of her abuser: “I absolutely remember pretending to sleep and avoid confrontation, so I could lay there and analyze my situation and read his energy to figure out what was going to happen next. I played asleep a lot.”

Trauma, in one form or another, has long been part of her life, Kehl said. Her father was an alcoholic, a big reason for the turbulent environment that she grew up in, Kehl said. “I found his dead body,” she said during our Zoom call.

Happiness came during her marriage, Kehl said. She and her husband rented a gorgeous, four-bedroom Salt Lake City house with high ceilings and a loft and jacuzzi. But then her husband died from an esophageal rupture. “He was an alcoholic and he bled to death in 2014,” Kehl said.

Soon after, when Kehl was still in shock and grief, she said she met the man who would eventually force her into sex trafficking. They started out dating and giving each other lots of freedom, she remembered. But then, about three months into the relationship, he grabbed her by the throat and lifted her in the air, she said. Then the abuse became regular.

That was when Kehl’s fear became so constant that she could barely think straight, let alone plan a route of escape, she said. “There were times when I tried to set boundaries and assert myself and take control,” Kehl said. “But he was hopping out of cars and bushes and sending text messages and saying he could see me through the windows.”

After he became violent, the sex trafficking started. He told her to go to a party and “do sexy things,” she said. He said they needed the money. She hesitantly obliged. But later, when she told him she wanted to stop, “it would be like he was holding me hostage with manipulation or anger—and lots of violence. I learned quickly that as long as I kept the money coming in, I could avoid a lot of physical injury.”

At one point, he punched her in the face and he broke her ribs. Another time, he beat her up in a bathroom and there was blood on the walls. The police came and took him to jail and her to an emergency room.

“You know this is never going to end,” Kehl remembers the emergency-room doctor saying as he pulled her stitches tight—so tight that she felt he was angry toward her, Kehl said.

Once, she tried to escape the abuse by getting on a bus and taking a four hour trip to St. George, Utah, where she rented a room in a stranger’s home, doing her best to hide from her abuser.

Then, she said, he began making fake profiles on social media to gain access to her, and he made threats to her family. “So I went back," Kehl said. "Then it got to the point where, everyone around me, everyone who cared for me a little bit? They became irritated with me and cut me off.”

The abuse stopped in 2016, when a police officer trained to deal with trauma helped Kehl feel safe enough to reveal the true story behind her continual hospital emergency room admissions for broken bones, concussions, and ruptured veins. At that point, Kehl was going in and out of jail for substance abuse. “That was my only escape, the only thing that gave me relief from my life,” Kehl said. The officer sat Kehl down, Kehl said, and told her, “I know someone is hurting you. I don’t believe you accidentally hurt yourself this much.”

Kehl said she began to sob.

“She rescued me by helping me put together a plan,” Kehl said.”I took the risk of her not being able to help me because I was just tired. I had nothing left—no people, no relationships, any sense of self. It was all gone.”

Today, Kehl has a full-time job helping an organization expand its treatment center for substance abusers. She is also a full-time student at Salt Lake Community College, where she is learning how to catch computer hackers. Her long-term goal: to work for an apprehension team that stops sex trafficking. Meanwhile, she is a volunteer at Soap2Hope, a Salt Lake City non-profit that helps sex-trafficked and other vulnerable women who are living on and working the streets.

Kehl, along with other volunteers, goes directly to high-risk hotels and other high-crime areas known for prostitution, sex trafficking, and drug abuse. “We hand out hygiene kits and try to strike up a conversation and hopefully establish enough of a relationship to provide resources or shelter or even an escape plan," she said. "I don't sleep very well on those nights at all—there’s massive amounts of adrenaline in my body at that point,” she said.

Kehl rents a three-bedroom house from her mother, a home where she lives with her 12-year-old son and helps to care for her 90-year-old grandmother. A sense of mutual trust and safety surrounds her, Kehl said. But the old terror of feeling trapped almost never stops.

It peaks in her nightmares and persists throughout the nights and even days. Sometimes she’s unable to breathe, and a whooping sound comes unexpectedly out of her throat. People turn around and stare at her like she’s some kind of freak, she said—“like they’re afraid of me.”

The unease and uncertainty caused by the pandemic has been especially hard to deal with, Kehl said, and she’s had to increase her trauma therapy visits to twice a week.

The therapist has been pushing Kehl to agree to a treatment that involves a kind of tranquilizer during her therapy sessions and to take prescription sleeping medication when she goes to bed, Kehl said, but Kehl said she’s “done with being treated like a trauma experiment.”

For now, she’s treating herself naturally, she said. At bedtime, that looks like an extended ritual that starts with an extremely hot bath. Then she opens some essential oils, usually a blend for post-traumatic stress syndrome designed by Doterra Oils and breathes as deeply as she can. After that, Kehl said, she drains the tub and takes a shower. Next, she fills the tub again and takes another bath.

“Sometimes I listen to soothing podcasts and meditations,” Kehl said.

Once she's dressed for bed, she said, “I take some melatonin and sleep oil and light some candles and I say a lot of prayers and set a lot of intentions. It takes about an hour. My body twitches then, too, and I have to go through this anxiety and I have to be forgiving of myself.”

Then, finally, Kehl said, relief flooding into her voice, “I fall asleep.”

Still, the nightmares come.

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

Nov. 10, 2020

Colleen Foley, Minnesota

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

FOR THE FIRST time in four years, 64-year-old Colleen Foley of Minnesota got a great night’s sleep—“ten solid hours,” the Minnesota resident said, relief flooding into her voice.

That was November 7, the day major media organizations announced the results of the presidential election. Joe Biden had won 290 electoral votes and become the new president-elect. Donald Trump had won 217 electoral votes. Though Georgia and North Carolina’s results had not been settled, Biden’s win was official, the Associated Press announced.

Four days later, Foley’s calm had all but evaporated, as Trump refused to concede the election.

Now the articles Foley is reading feature national newspaper columnists wondering about what had been previously inconceivable to Foley: Would Trump try to appoint electors to ignore the election results and vote for Trump instead?

“My couple of days of thinking, ‘Biden’s got this,’ have gone away," Foley said. “Because now, though I’m confident Biden won the vote, I know that Trump is going to create hell on earth for us—it’s going to be complete and total chaos.

Foley, a retired insurance liability claims specialist, is back to waking up throughout the night, pacing through her home and scrolling through her phone for newspaper accounts about the threat to democracy in this country and rising COVID -19 infections and deaths.

“I try to be careful,” Foley said. “I always mask up. I’m not as worried about myself but I’m worried about my stepmom, who is 81 and living in assisted living.”

There have been more than 242,000 deaths and 10 million reported COVID-19 cases in the United States since the start of the world-wide pandemic in March, according to an online graphic that is produced and updated by the New York Times and that Foley tracks daily.

Foley lives in a tidy, one-story, three bedroom home in a suburb about 20 minutes away from Minneapolis. She surrounds herself with ways to enjoy life. There’s a water fountain on a deck filled with begonias and impatiens that bloom in the spring; she has five rescue dogs, two cats and a 30-year-old Arabian horse, Sticky, who she boards at a barn.

Every day, she works out at a fitness center, and six days a week, she visits Sticky at the barn. These activities bring tranquility while she engages in them, she told me. But within a few hours later, the anxiety about the fate of the country returns.

“Last night I didn’t sleep well at all,” Foley said on November 11. “I tried to go to bed early and get some good rest but I ended up doomscrolling on my phone. I probably got a block of about five hours of good sleep—the rest was just getting up and down. I should have smoked some weed.”

Instead, she obsessed about the potential of a civil war in America.

“I don’t know what form it will take on in these modern times,” Foley said. “But the people who are backing this crazy lunatic aren’t backing down either. I'm just confounded by what is happening in this country.”

For the first time in her life, Foley, a woman who supports strict gun control laws, is considering buying a pistol.

“I was talking to my sister the other day and we were like: ‘Do we need to get a gun?,’ Foley said.

“I mean, did you ever think that we would be here today? It’s bizarre to think that we may have to fight against our own fellow countrymen.”

Foley’s chronic insomnia started in 2016, the day Donald Trump was inaugurated, she said.

“On the first day Trump took office, my daughter went to school and some of the other kids were asking her: ‘When are you going to get back on the boat?’ ” Foley said.

Foley adopted her daughter, Emily Foley at 13 months, from China, raising the toddler single handedly while working full time—always vigilant about her child’s mental and physical well being in a country known for its history of racism.

So when Foley heard Trump speak demeaningly about immigrants—before as well as after the election—Foley’s anxiety skyrocketed. She reassured her daughter that she had the necessary paperwork to stay in the country—that she was, indeed, safe.

But then came the Unite the Right rally in 2017 in Charlottesville, Virgina, and the killing by a white supremacist of a woman who was counterprotesting there. From Foley's perspective, Trump made “a call to arms for the supremacists," saying that there were "very fine people on both sides."

Shortly after that, Foley booked an appointment with a psychiatrist for prescription medicine to help her sleep, she said.

“I would fall asleep and have these lengthy, horrible nightmares,” Foley said. "I would go to bed early but easily stay up until 3 or 4 a.m.”

Foley has protested and marched against the Trump administration three times: once in a women’s march in St. Paul, once at an immigration rally in Minneapolis and again at an anti-gun rally in St. Paul. Still, the original dosage for her sleeping medication needed to be doubled before it began to touch the helplessness and uncertainty that she felt, Foley said.

“I would like to be able to wean myself off them slowly as things become more stable,” Foley said. “Hopefully that will happen when Trump is gone and Biden can wrap his arms around the severe COVID pandemic and try to unite the country, because we are so divided right now.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

Oct. 27, 2020

Stew Singleton, Utah

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

EVERY MORNING BETWEEN 6:30 and 7, for at least the past month, a driver in a red SUV has blasted his horn in the exact moment he passes Stew Singleton’s RV, which is parked on 17th Avenue in Salt Lake City.

It’s happened so many times that Singleton, lying in bed inside his 20-foot, 1987 Toyota Dolphin rig, often awakens in anticipation of the noise.

“It’s really scary because when you are in an RV there isn’t much of a shield between you and the world—just a piece of glass or a thin metal wall,” Singleton said. “It feels like whoever is making noise is three feet away from your bed.”

Other mornings, when the 30-year-old hasn’t been able to will himself to consciousness before the blare, Singleton bolts awake after it, as startled as he is angry.

On those days, Singleton glares out of his RV’s bedroom window to stare at the offending SUV driving down the otherwise quiet residential street, near a public park.

Singleton, who said he attended high school in Salt Lake City and then studied acting at the University of Utah until he got kicked out for “attendance issues,” earns a living of about $2,400 a month in a multitude of ways: sometimes as a DoorDash employee; sometimes as a hospitality worker. When he can borrow his girlfriend’s Subaru he also works as an Uber driver—she has been driving her own vehicle behind his RV as the couple attempts to follow the warm weather across the country.

For him, the nomadic lifestyle, something he has dipped in and out of since 2015, he said, “is a loophole in society.”

“It's a way of getting around rent and bills that people assume are mandatory and that you are supposed to spend your day and your life being able to pay.”

I couldn’t find statistics that include all working folks who choose the nomadic lifestyle. But according to a study from MBO Partners, an organization that connects independent workers with private companies, the number of traveling workers it calls "digital nomads" has risen from 7.3 million to 10.9 million in the last year alone.

With all the freedom that Singleton experiences in the lifestyle, I asked him why he simply doesn’t park his car someplace else—somewhere without an SUV driver intent on waking him up every morning.

“So, it’s half a mile from the high school that I graduated from," he said. "It’s on a quiet side of the Salt Lake Valley. It’s a clean street. The overpass is nice because the white noise of the cars is really soothing. It’s perfect, except for this one person who wants to make it known they don’t appreciate my presence in this neighborhood.”

Singleton said he paid $6,000 for his rig, which is white and beige with a BIDEN/HARRIS poster taped over its back window, and then spent another $10,000 upgrading it. Neither pretty nor dilapidated, the setup has drawn a lot of negative reactions, Singleton said.

“A lot of people see me with my solar panel and the 10K I put into the RV,” Singleton said, “and they think of me no differently than a homeless person begging on the street.”

Last month, a homeowner sprayed Singleton and Singleton’s dog, Ralph, with a sprinkler.

“We were standing in front of our RV,” Singleton said, “parked near this guy’s house.”

Another man looked at a Black Lives Matter sign that Singleton had taped over one of his RV windows at the time and screamed: “Black lives don’t matter! Fuck you and your dogs!”

At the time of our interview, parking on Salt Lake city streets in a self-contained RV was legal. However, on November 1, those laws, which had been suspended in March, are scheduled to change.

The police have come to Singleton’s RV to answer calls about “suspicious behavior” at least a couple of times in the past few months, Singleton said. “But I have never been cited or arrested for anything, because I haven’t done anything,” he said.

The continual experiences of people telling him “You can’t park here,” or “The last thing we need is another RV around here,” makes him feel like he’s in a fight against the world, he said.

“Just by the choice of the way I have been living, it’s as if I have been drafted by a war against regular suburban people,” Singleton said.

It’s a fight he’s determined to win.

“I worked in this city and served in this city, and if I wanted to buy an RV and live on the side of the street, I am going to do that,” Singleton said.

Within the confines of his 20-foot home on wheels, Singleton said, he tosses and turns at night, whether it’s because he’s thinking about his days, or he’s waiting for the sound of the horn to blast through his home again, or he’s fuming over the fact that it just did. During those times, his mind often turns to plans of revenge against the suburban honker.

“My plan is, I’m going to be awake at the time that he usually comes to honk. And as soon as he honks, I’m going to jump out of the RV and chase after in the Subaru and lay on the horn for a while.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

Oct. 13, 2020

Michael Waldren, California

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

BEFORE DONALD TRUMP became president of the United States, before COVID-19, before Michael Waldren says he continually worried about “the inevitable collapse of the world,” bedtime was actually soothing.

Back then, Waldren, who lives in Long Beach, California, could go to bed later in the evening, assured that he was going to sleep through the night. Back then, he didn’t have to drink wine or beer or take sleeping supplements to calm his mind.

“Now my days are non stop. From the moment I wake up to the moment I fall asleep, there is no room for me,” says Waldren, who is 39. “Falling into bed is about embracing the only portion of the day that I own.”

Waldren is a Los Angeles attorney who represents low-income domestic violence victims. His wife is an emergency-room doctor. Because of the pandemic, the couple is homeschooling their two children, ages 4 and 7, and Waldren is working mostly from home, where the family has put him in charge of cooking, laundry, and bedtime stories.

Sometimes, by his own bedtime, Waldren is so tired he can’t muster the strength to brush his teeth. On those days, he says: “I rinse my mouth out with mouthwash and collapse into bed.”

At first, sleep comes hard and fast. But it generally lasts only 3 to 4 hours. After that, Waldren says, the rest of the night belongs to the part of his mind that insists on preparing for the next day’s challenging case or the anticipation of a difficult opposing counsel.

The stakes are high, especially right now in the midst of the pandemic, as this is a time when domestic violence victims have fewer resources than ever. Domestic violence shelters are receiving less funding in tight financial times, and homelessness is increasing.

Desperate client calls and texts come through at all times of the night. Sometimes prosecutors won’t prosecute the abusers because they don’t want to send perpetrators to the Men’s Central Jail—where the odds of contracting COVID-19 are extremely high.

“I stew and I fester,” Waldren says. “And I ask myself: ‘Dear God, when will it ever end?’”

Perhaps the most surreal part of his life is working around his children at home, where he sequesters himself in a corner office away from them, so as not to expose them to the trauma inherent in his career. “But it still happens,” he says. “I will be reading a declaration about a child’s biological father abusing him/her and my own child will be tugging at my pants leg, trying to show me a drawing.”

When he awakens after those first three or four hours of sleep—somewhere around 2 a.m.—Waldren says he often ends up scrolling through his phone for the latest bad news. On Monday he read an article in the New York Times headlined: California Republican Party Admits it Placed Misleading Ballot Boxes Around State. That was enough “tangential trauma” to keep him up for the rest of the morning, Waldren says.

Coffee kept him awake the rest of the day, for a while. But then, he says, it did what it does at such high and continual doses: it “over caffeinated me and gassed me out” and kept him from sleeping more than a couple of hours a day for four or five days straight.

Waldren’s bedtime is at 9 or 9:30 p.m. But his children wake up at the non-negotiable time of 6 a.m. Then, he says, he thinks the same thought he always seems to think these days: “I don’t know how much worse it can get. But every day, we get some form of new worse.’”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

September 29, 2020

Sylvester Miller, Illinois

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

MORE OFTEN THAN not, the exhaustion that Sylvester Miller feels when he tries to fall asleep after work is so layered, so deep and so visceral, that the pain of it keeps him awake.

“I have to pop pain pills before I go to work, and also sometimes after,” Miller says.

Sure, the pills eventually help Miller fall asleep—usually around midnight or 1 a.m., But they also keep him groggy when he wakes up in time to go to work—around 3:30 a.m.

And since Miller, 51, works seven days a week—40 hours Monday through Friday hauling 50 to 60 pound planks of wood at a manufacturing plant and then 16 hours Saturday through Sunday as a security guard—the cycle of exhaustion never ends.

“I have to be physically on top of my game in one job and mentally aware in the other," Miller says. "On Mondays and Tuesdays I am dragging. And then when I try to get to sleep, my mind is racing.”

It is 4 p.m. on a Tuesday. Still in his work clothes, Miller sits on the edge of his bed to talk. I can hear the tiredness in his voice, a gravity that slows his words down and makes them sound creaky, like a rusty hinge. “I’m so tired," he says. "Lord knows, I’m exhausted.”

Just five months ago, Miller emerged from an eight-and-a-half-year period of homelessness. Before that, he spent a decade in and out of jail and prison for dealing drugs, he says. Now, though, he says his life “has taken a 180.”

“Everything is about work," he says. "I need to pay my bills and be responsible. And coming out of homelessness—well, there are a lot of things that I have never done before.”

This is the first time in his life that he has paid rent, he says. He lives on the far West Side of Chicago, in a narrow three-bedroom, one-bath apartment that he shares with two other men who work. Not so long ago, Miller lived with his girlfriend, the mother of his two now-adult children. She paid all the bills, Miller says. He talks about that time with surprising transparency.

“She had her own place. I didn’t," he says. "I moved in with her and we ended up having two kids together. I was still a hustler. She was responsible for the bills and everything. I never took the time out to do any of that. I just did what I wanted to do and she moved on.”

Now Miller is single—a state he hasn’t experienced in so long that it feels like another first.

“We broke up almost two years ago," he said. "That relationship just meant so much to me. I feel guilt-ridden because I think I let my family down.”

The loss is also part of the pain that keeps Miller up at night.

“I’m used to sleeping next to her. I’m used to being around my family. This is a new world for me. Even though I work a lot, I’m at a lonely place.”

Letting go of old friends has been a necessary part of his recovery, Miller says. So has the support of good-hearted church folks who made sure he had clothes and food, as well as friends and family members who allowed him time on their couches. Yet many relationships have grown strained, as Miller says he knows that if he kept them, he would likely end up in the life he has worked so hard to leave behind.

Making new friends has been more difficult than he anticipated: “There are some good men at work. But we talk and then we go home.”

His own family is spread out across the country, he says. And besides, they have never been particularly close.

“Everyone claims to be so busy,” he says.

His manufacturing job pays $13 an hour and his security job pays $14 an hour, says Miller, who blames his lack of education—he never graduated from high school—for his low wages. He knows he could go online and work toward his diploma. But the draw to make more money is too strong to stop and do that.

“I want to buy a house and life insurance in case I die, so that I can leave my family money,” he says.

Recently, lab results showed blood in his urine, Miller says.

“God helped me beat prostate cancer four or five years ago," he says. "Now I am worried the blood that showed up in the scan means that the cancer is back. I try not to think about it.”

Thoughts of death are also part of the pain coursing through him at night, he says.

“I have to believe there is a God," he says. "I know there is a God. I beat homelessness and prostate cancer. I know my health and strength come from God.”

When he can’t sleep, he gets up at night and plays his “old dusties”—classics from Earth, Wind & Fire or Marvin Gaye. Or he gets up and walks around his room. Or watches a movie on his phone. The next morning he feels as if he has been in a fight, he says, his eyes are so red and swollen.

Still, it is as if he can’t work enough. This week Miller plans to start a third job working four or five hours on weeknights for a cleaning business. It pays $460 a week—enough to allow him to start saving a decent amount of money.

“Everything is about work," he says. "I got to keep it all moving.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

September 15, 2020

Harriet Robinson, Colorado

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

SOUTHERN COLORADO — These days, Harriet Robinson’s anxiety pills are in a zippered canvas case on the stand next to her bed, an increasingly faint reminder of her three-year effort to ensure the peace she needs to get a good night’s rest. She’s down to just one of the small, round pills every other day.

“In three weeks, I will be finished with them,” Robinson said from her king-sized bed, decorated with leopard-print blankets.

An actress and satirical writer, Robinson, 60, knows she could likely write a story about her odyssey with sleep. The question is, would it be a comedy? Or an anxiety-filled tragedy?

It all started three years ago, when an allergic reaction to a medication her doctor gave her for a mild, intermittent health issue sent her to an emergency room in southern Colorado.

“I couldn’t breathe, was lightheaded and broke out into a rash,” Robinson said. “I had to call 911.”

An E.R. doctor prescribed a steroid to stop the reaction. But when Robinson stopped taking the steroid, her heart began to race wildly. She was diagnosed with tachycardia, a condition defined by episodes in which the heart beats faster than 100 beats per minute. Robinson’s resting heart rate escalated as high as 136.

“It was very scary—I felt helpless and out of control,” Robinson said.

The Colorado resident started staying up at night, Googling her symptoms, wondering if she actually had a disease that was going to kill her. In the midst of that, Robinson confronted the inevitability of her death. And her anxiety skyrocketed.

“I couldn’t get through to people how much in a panic I was," she said. "In truth, it was all about the idea of death and that I was afraid my life was threatened and that I was going to die.”

The fear led her down a never-ending rabbit hole of questions.

“What am I afraid of about death?”

“Is it the end of everything?”

“Is there an afterlife after this or not?”

Robinson began going to therapy and studying with a woman who had had a near-death experience and was teaching an online class That helped. What didn’t help: the doctors who kept telling Robinson that her problems were all in her head.

“And I kept telling them: ‘But I am mentally in distress because my heart is racing.' It became a question of which came first—the chicken or the egg.”

Physical healing began in 2017, with prescribed sleeping medication, Robinson says. After five or six weeks of living in a sleepless state that caused her to feel “hyper-aware of everything,” Robinson’s mind was finally able to relax enough to slip into unconsciousness.

A substantial problem, however remained: She would wake up with the same fear and anxiety she'd had after the original trip to the emergency room. And as those symptoms continued, another symptom formed—depression. For that, Robinson relied on her husband’s steady stream of pep talks, an anti-anxiety prescription, and continued therapy.

At that point, sleep—even when forced through a medication—became a refuge.

“I was like waiting out the agony of the day, of being awake and being alive and feeling as horrible as I did. I would always ask myself: ‘How long do I have to wait until I can return to sleep?’“

Weaning herself off the sleeping pills caused new bouts of sleeplessness, as Robinson worried that her body wouldn’t be able to fall asleep without them. Still, after nine months, she was done with them altogether. Now she's approaching the end of the anxiety medication as well.

Along the way, she has learned a lot about herself—namely how much her body needs sleep. Now she winds down with mindfulness meditations, calming music, a soothing view of the Rampart mountain range, and the comforting snore of her Shih Tzu, Josephine ("Jo Jo," for short). She breathes a soft flow of oxygen through plastic tubing at night, to help her cope with her residual anxiety, as well as the 8,500-foot altitude at which she lives.

“I am so grateful to be able to sleep now,” Robinson said. “Sleep is a basic human need that I no longer take for granted.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

August 25, 2020

Yvonne Ryans, Utah

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

EVER SINCE THE Salt Lake City police dog attacked her son in April—biting into his leg while an officer told the dog, “Good boy,” according to a recently released police video—Yvonne Ryans says she has been a nervous wreck. Especially at night.

For the first time in her life, she is taking sleeping pills, she says. But her worries are stronger than the medicine; her thoughts about her son, who has undergone multiple surgeries as a result of the attack, never stop.

“I’m OK during the day,” she said, “But my fear comes at night. I start to shake uncontrollably.”

Ryans, 64, and her 36-year-old son, Jeffrey Ryans, are African-Americans. Before her son was attacked, Ryans says she never worried about herself or anyone else in her family being victims of possible police brutality.

“I remember that happening to John Lewis and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. when they were fighting for our voting rights. But in this day and age—I had never heard of such a thing.”

An officer’s body-cam footage released earlier this month, shows that on April 24, a K9 officer ordered his dog to bite Jeffrey Ryans while he was kneeling with his hands in the air, then again while he was lying on the ground with another officer on top of him, as Ryans screamed in pain. The police had been responding to a 911 call regarding possible domestic violence, said Detective Greg Wilking of the Salt Lake City Police Department. The story about what happened when officers arrived on the scene has been shared by media outlets worldwide.

Jeffrey Ryans has taken steps to sue the Salt Lake City police after alleging that officers used excessive force when they ordered the police dog to repeatedly attack him, according to an article in the Salt Lake City Tribune.

A day after the release of the video, the Salt Lake City Police Department suspended the apprehension portion of its K9 program, meaning that the dogs are not being used for biting, but they are being used in other ways, Detective Wilking said.

“With the release of that video we had to react and we’re going to take a look at the procedures and policies,” Wilking said. Meanwhile, the officer who ordered his dog to bite Ryans has been placed on administrative leave, Wilking added.

Yvonne Ryans, a retired sales assistant for Channel Four news station, said she watched the airing of the video with Jeffrey.

“I said: ‘This is you?’ There is yelling and screaming and the dog is still biting and the officer is saying, ‘Good boy'? Is this really my son? This is my son?”

But no matter how many times she asks herself the question, the shock remains as impenetrable as the night that Jeffrey called her to tell her he was in trouble.

“He told me, ‘Mom, I’m going into surgery.’ And I said, ‘What are you talking about?’ And then I heard a cop in the background yell: ‘Get off the phone!’”

“I just sat there, numb," Ryans said. "I didn’t know what to do.”

Hours later, Ryans says she picked Jeffrey up at the jail—police took him there after his surgery—and brought him to her two-bedroom condo. He’s been living with her ever since, she says.

“He goes to the doctor every Thursday because it’s still an open wound and they have to scrape the dead skin and try to get new skin to form. The first time he went, I went with him. When they pulled the bandages off, it was just oozing blood and pus and water and it was just horrifying—horrifying. I was sick to my stomach.”

Ryans wishes that “all this was over,” but she has no idea what her new normal will look like, and that’s one of the main anxieties that wakes her throughout the nights. Her gut tells her that her son will need to leave Utah to escape the public scrutiny and outrage that the attack has caused.

With her unwavering faith in God and the support of her friends, who regularly call her to go walking and golfing, Ryans says she has a substantial amount of support. She has noticed, however, that the friends who call her are Black. Her white friends haven’t reached out, she says.

“I think they might be afraid to call me and I don’t think they really know what to say. And I feel like they will never experience what I have experienced. Because I don’t think they would put a dog on a white man.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

July 17, 2020

Greg Young, Utah

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

GREG YOUNG STOOD over a body bag containing his 46-year-old friend, a victim of COVID-19. It was July 9. Two Labrador retrievers behind the front gate of the man’s home cried as their owner was wheeled into an ambulance. The memory of that howling, along with the unstoppable wondering what his friend’s last moments were like, followed Young to his home in North Ogden, Utah. There, he hugged his boys goodnight, told his wife he was going to bed early—it was just 9 p.m.—and collapsed into his king-sized bed, where he clutched his pillows and tried to sleep.But a nightmare about death, along with another dream about a woman who wanted Young to buy the Christmas trinkets she was selling—and then cried inconsolably when he refused—kept Young from consistent sleep.

When he got up Friday morning, he donned a baseball cap, barely noticing the dark circles under his eyes.

“Yeah, I’m a little tired,” Young said. “But isn’t everybody right now? I think this whole COVID situation has really made people tired.”

Young, 49, tries to counteract that negative impact by helping people out whenever he can: in his personal life, where he says he is devoutly spiritual, as well as at work, at the offices of the transitional services for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Salt Lake City. He is the general manager there, helping to meet the needs of an impoverished population that includes refugees, immigrants and people coming out of incarceration.

But 2020 has repeatedly brought Young to tears, when despite his efforts to intervene, three of his friends have unexpectedly died.

The first friend was a colleague, Gordon Smith.

“He took his last breath in my arms,” Young said.

“There were three missionaries in my office and everyone was joking around about the conspiracy theories surrounding COVID,” Young said.

To support the group's levity, Young offered to make a donut run. When he returned to the office, he saw his friend “sitting in a chair, with his head tilted back, making gurgling sounds.”

“I started doing CPR and security came and I cradled him in my arms and yelled: ‘ Elder Smith come back!’ And then he took his last breath. I went into my office and sobbed.”

That was in March. Before that, in February, came the death of Justin, a man whose last name is not being used to protect his identity. Justin was a homeless man in his early 30’s whom Young was mentoring.

He had been out in the streets since he was a teenager, Young says.

“He was hooked on drugs," Young said. "He hustled people for money and he was regularly getting picked up by the cops.”

Sometimes the two sat men in Young’s office, talking about life and all its hardships. “One thing that I have learned is not to judge,” Young said. “Because, yeah, some of my clients have made bad choices. But don’t we all?”

Young tried to coax Justin into detox, but to no avail. One afternoon at work, Young got a call that Justin had overdosed. Police found his body near a downtown building vent, where Justin had apparently huddled in an attempt to be near the warm air that the vent was blowing outside.

Young felt awful. Yet he says he knows in his heart that in death, there is a release of suffering. “Their spirits are soaring and they are probably happy that they aren’t having to deal with the tumultuous life that we live in.”

The third friend who died was Mark Stout, the man who contracted COVID-19 earlier this month. A husband and father of three, Stout was a self-employed truck driver who lived in Harrisville, Utah. Young got the news of Stout’s death the day it happened.

“My bishop called and said: “Greg, there is an ambulance and three cop cars in front of Mark’s house,” he said.

Stout had texted Young just a few days previously: “ ‘I have COVID and I think my family has COVID as well.’

“I texted him back and said: “What can I do to help?’

“There is nothing you can do,” Stout texted back.

Nevertheless, Young sent more texts. Stout didn’t, or couldn't, respond.

Before the COVID, Stout had told Young that he had several near-death experiences, as he had nearly died in car accidents as well as industrial accidents.

“Greg, I have nine lives,’ ” Young says Stout told him. “‘I don’t understand why I keep staying on this earth. What is my purpose here? I keep getting saved.’ ”

But the medical complications he endured, which include diabetes, left Stout vulnerable to COVID-19.

When Young drove to Stout’s house, the police wouldn’t allow Young to enter the home, where Stout’s wife and two children were quarantined inside, Young says.

“I told the police: ‘I am his friend, can you at least let me wheel him out so I can say my goodbye?’ ”

Standing over his body, Young says he told Stout that he was sorry he couldn’t be with him one last time.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Young says. “There is a lot of good in this world. But every day I see suffering. I see people who have to go through very difficult circumstances and I wish I could rescue them all. But I know I can’t do that. I can’t control things like that.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

June 26, 2020

Joe Vaughn, Alabama

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

IN THE SLEEPLESSNESS of the late nights, Joe Vaughn, 40, leaves his sleeping wife and heads outside, where he immerses himself in something he calls “my own enlightenment”—a kind of life review, he says. Here, he tries to figure out how to escape the matrix of his life as a Black man, a life in which he feels he is constantly struggling to make progress.

A physical education teacher with the Montgomery Public Schools, Vaughn is the father of three children. The family lives in a four-bedroom house, a rental in a working-class neighborhood.

People tell Vaughn that he has come so far, overcome so much. And that is true. But Vaughn’s focus is on the future, which with his hard-earned logic, inevitably brings him to thoughts of death.

His own death. The people he watched die violent deaths throughout his childhood. His brother’s murder three years ago.

“He was out on the front porch cleaning his refrigerator when someone shot him,” Vaughn said. “That broke me.”

These are the thoughts that keep Vaughn up at night. Vaughn’s parents both struggled with substance abuse, he says, and as one of six siblings, he grew up in a housing project where he was faced with drugs and violence and prostitution. His mother had been sexually assaulted when she was a child and never received the emotional support she needed to break free from that trauma, he says. Then she was exposed to drugs. His father, Vaughn says, was never a permanent part of the picture. At 5, Vaughn went to live with his maternal grandmother, in the Trenholm Court housing projects of Montgomery. At 8, Vaughn was nearly killed by a young man who used a broken bottle to cut him on the neck, less than a centimeter away from a major artery.

“I didn’t think I would live to be 40,” Vaughn said, matter of factly.

Vaughn says he followed the rules people told him to follow—he stayed in school, he got decent grades and played sports—but his main motivators were that he did not want to die and he did not want to spend his life in prison.

Now Vaughn wants to overcome the systematic barriers that keep him and so many Black people he knows from thriving: the knowledge of how to attain good credit; the financial leverage to secure a decent bank loan; the knowledge of how, when the time comes, to help his children do the same.

“My son asked me a couple of years ago: ‘Do we have a college fund set up for me?’” Vaughn said. “I told him, ‘No son, but I am doing the best I can.’ ”

That exchange continues to keep Vaughn awake at night.

“I feel if I die, I want to have an inheritance to leave behind. I wasn’t put here on this earth to say ‘I overcame drugs.’"

In addition to his job as a teacher, Vaughn is also the founder of Underdog Consultants, a company through which he aspires to help youths lead their best possible lives. He carries the company’s program, “Aspire DREAM BIG,” to audiences and groups that invite him to speak.

“I want to move thousands of people forward like I have seen W.E.B. Du Bois, Malcolm X, Dr. Martin Luther King, and Dr. Eric Thomas. Then I will know that I have succeeded. That is something that causes me not to sleep. Because that is the thing about death. You have to stay ahead of it.”

Vaughn has gotten life insurance, he says. But he doesn’t own any property, he points out, and that’s another fact that keeps him awake.

He worked for years to clean up credit problems after his mother used his personal information to get her electric service and then did not pay the bill. “My mom was not given opportunities. Because she was not given opportunities, she robbed me of opportunities,” Vaughn said.

Despite his solidity and steady employment—Vaughn has been with the Montgomery schools for 16 years—the banks continue to deny him low-interest credit and low-interest loans, he says.

“I don’t have the generational foundation to break out of the rat race,” Vaughn said.

There is a huge tree outside his home, Vaughn says, a tree he has dubbed “the limbs of life.” During the sleepless nights, Vaughn stares at that tree, thinking about how, after four decades of life, he is only beginning to learn things that could have moved him and his family forward if he had known about them earlier. One of his most recent findings, for example: that it is possible to assist your child in building credit by adding them to a parent’s credit card.

“A white lady at the bank told me that. I was like, ‘You can do that?’ ”

In addition to taking classes on intergenerational wealth, Vaughn says he is just beginning to learn who he is—beyond what his own elementary school teachers taught him about how he comes from a lineage of slaves.

“I felt for so long like I wasn’t anybody. Now I feel so inept culturally—like, as a Black person I don’t really know who I am,” Vaughn said. “I had not heard about the Tulsa riot or the Black Wall Street until two or three years ago. I was blown away. There are so many Black pioneers.

“And here is the thing: If I don’t have a cultural identity and I don’t know who I am, I am going to go forth in the world with blinders on. This is the kind of thing that keeps me up at night.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

May 29, 2020

Rachel Hoang, Utah

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

A BAD NIGHT’S sleep can meet many definitions, says Salt Lake City hair salon owner Rachel Hoang. There are the times when the sinus headaches hit, for example. And then there are the times of Major Stress. Like Sunday, May 17.

“I had a friend staying with me because she was leaving a bad situation with a boyfriend and so she had been hanging out with me over the weekend in order to separate herself from this person. My house was a safe space.”

On top of the “normal stresses of the pandemic,” Hoang said, it was the last week of school for her kids, and it was the week she was reopening her business, Curly Hair Studios. Add to that the pressure she felt to try to help her friend and it definitely all equaled Major Stress.

Midnight.

Hoang’s dresser fan and ceiling fan whirred, creating a cold white noise that served as a comforting contrast to the 20-pound weighted blanket she lay beneath. Still, one thought raced repetitively through the 36-year-old’s mind:

“Who else needs help?”

Of course, Hoang wondered if she had best helped her friend. Had she been supportive enough? Or should she have been less supportive? Her friend was planning on returning to her own home the next morning. Would she be safe?

“I analyze the situation until it is literally dead on the ground," Hoang said, "then I realize I am not responsible for other people’s lives or actions.” Sometimes, the white noise helps to drown it all out. But that Sunday, the fans weren’t enough. Nor was the two-hour Epsom salt soak in her bathtub jacuzzi. Or watching Frozen on Netflix with her three boys.

Now, past 1 a.m., Hoang’s husband was downstairs watching television. Hoang lay down and closed her eyes, her mind drifting to a recent confrontation with a client. Hoang had been suited up in a plastic face shield as well as a mask.

“The client suggested that neither of us needed to wear a mask.” Hoang had already sorted out her answer: “The Health Department requires the stylist to wear a mask.”

The client quickly acquiesced.

“She knew I wasn’t going to change my mind.”

Still, when Hoang thinks about conversations like that, she can’t sleep.

“For weeks before I re-opened, I had all these conversations in my head ahead of time so I prepared myself with each client and decided which stylist should work with whom so we could support each other.”

One a.m. Everyone in the seven-chair salon is sticking to pretty strict rules: No more than four chairs utilized at one time. No more than one guest per stylist. No one waiting for appointments. The bathroom is sanitized after each client uses it, and the front door of the studio is kept locked so that stylists greet their guests one-on-one.

“We’ve also made a pact amongst ourselves,” Hoang said, “Until this is over, we will be very careful in our lives so we don’t bring it to each other or our guests. We’re not going to large gatherings and we’re not going to stores unless we need to.”

Three a.m.

Because of the requirement for social distancing inside the 1,300 square foot studio, Curly Hair Studios is operating at 50 percent of its pre-COVID rate. Thanks to federal grants for businesses, the drop in income hasn’t wrought havoc.

“But there is an overwhelming amount of people trying to get in, and you just can’t help all of them,” Hoang said.

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.

May 13, 2020

Mark Dodson, Utah

By Lori Teresa Yearwood

MARK DODSON, M.D., sat down at the dinner table in his house in an elegant Salt Lake City neighborhood called The Avenues and ate a meal that his wife cooked from scratch. He doesn’t so much remember the meal, but he says it was likely fish or chicken—followed by water, which he knows to be true because that is the way she runs their household; like clockwork, every breakfast and dinner is made from scratch followed by water.

Dodson, 58, has been working as a gynecological oncologist for 25 years. He would do the surgery at LDS Hospital in the Avenues, which is only two stoplights away from his home.

The next day, he would perform surgery on me—“the debulking,” he and his medical colleagues called it. “Taking out people’s organs is what every surgeon dreams of doing,” he said afterward. “This is what I do for fun. I knew yours was going to be huge. It’s a surgeon’s dream because the potential of being cured by what I do is real. I do 25 or so of these kinds of surgeries a year. The rest are simpler.”

After dinner, Dr. Dodson drank his espresso and reached into a plastic bag for a few dark chocolate Dove medallion chocolates. Then he read a good book. That night it was The Poisoner's Handbook: Murder and the Birth of Forensic Medicine in Jazz Age New York, by Deborah Blum.

“They would poison people and find ways not to be found out,” Dodson said. “That led to the development of the medical examiner’s office. That used to be a very political job. People paid the medical examiner’s office not to notice that someone had been poisoned with carbon monoxide, for example.”

Dodson is a red-headed man with blue eyes and a physique shaped by regular core-strengthening exercises and faithful time on his elliptical. He grew up with the flowering dogwoods in the backwoods of Tennessee, where he was raised by a full-time schoolteacher who, in addition to working, made breakfast and dinner three times a day, seven days a week.

“My father worked, too, but I saw that women work twice as hard to get to where a man has to get,” Dodson said. “That is why I specialized in female surgery. I want to help women.”

As it always does, sleep came easily to Dodson—“within 2–3 minutes of laying my head on the pillow,” he told me. The room was dark without noises, the Sealy Posturepedic mattress and pillow delightfully firm. He had to get up only once, to take out Ricki, his 8-month-old standard poodle, for a bathroom break.

“I always sleep well," Dodson said. “The scary part for me is what I can’t control. I knew I wasn’t going to lose you on that table. The scary part for you is what you can’t control.”

“How Did You Sleep Last Night?” is an ongoing series.