A historic driving tour of the presidents

Indignity Vol. 5, No. 30

HOLIDAY LEFTOVERS DEP'T.

Presidents' Weekend, February 2010

In the snowy winter of 2010, your editor celebrated Presidents' Day by setting out on a family tour of presidential homes within a manageable weekend-trip distance of Silver Spring, Maryland. He wrote about the experience on his personal website, then lost his personal website in a domain-renewal blunder, then came away from it all with a salvaged text archive of the site's contents. This Presidents' Day weekend he remembered it existed, so Indignity, taking the day off from doing new work, presents the recovered account.

Mount Vernon, Feb. 13, 2010

The walkways at Mount Vernon are unpaved, in fidelity to the conditions of George Washington's time. The dirt is a sandy mix reminiscent of a racetrack, with good enough drainage to be merely sloppy instead of pure muck. Pavement might have taken less effort.

We were too late to get the Presidents' Weekend breakfast of hoecakes with a Washington impersonator.

Washington's taste in decoration was gaudy and self-conscious, including a room with expensive verdigris-green paint and agricultural emblems carved in the woodwork and marble. Martha Washington, who was in charge of decorating their bedroom, had much simpler and better taste. After his death—you can see his bed, in which he expired—she abandoned the room and used a bedroom in the attic.

The slave quarters next to the greenhouse, which were the nicer slave quarters, didn't look so uncomfortable till one realized that two-thirds of the bunks were missing. Otherwise it would have been too dark and crowded to see into the room.

Monticello, Feb. 14, 2010

The Great Emancipator's home being out of automobile range, we settled for the Great Non-Emancipator (b. April 13). The very first thing you get, on going inside Monticello, is kind of a perfect metaphor for Thomas Jefferson. He had a complicated clock built through the wall over the front door, with an hour hand showing on the porch side, then a full clock face on the inner hall. From that inner clock, a set of weights and cables spans the room, slowly descending to mark the progress of the days of the week, down a wall marked SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY—

And then the weights pass through a hole in the floor, down into one of the provisioning cellars, where he had to put SATURDAY because the rig ran out of room.

So paint ABOLITION on the cellar wall, too, and your American Sphinx seems more familiar than mysterious. He meant to do something about slavery, but he was broke, and the farm wasn't covering his debts, and there was always a silk bedspread or a simultaneous-writing machine to buy from the Continent, and he never got around to being able to follow through. Write the Declaration of Independence, but let other people take up arms against the Crown, then try to spare Virginia from paying an equal share of the war debt. Run for president on the principle of a limited central government, then spend $15 million on the Louisiana Purchase. Denounce the despotism of slave ownership while light-skinned children with familiar features run around the plantation. What would America be, or what would it have been, without good intentions?

Ash Lawn–Highland, Feb. 14, 2010

Every visitors' center at a presidential estate has two core functions: to sell tickets and to block the view of the house for people who have not bought tickets. Just down the Thomas Jefferson Parkway from Monticello is Ash Lawn–Highland, the home of James Monroe. The last little turnoff on the way is called James Monroe Parkway. Admission to the fifth president's house is $10, and Monticello has already consumed the morning and half the afternoon, with James Madison's Montpelier still waiting on the way home. In place of a guidebook, there is a one-sheet. Hello and farewell, President Monroe!

Montpelier, Feb. 14, 2010

James Madison was a little man, the guide said in the parlor of Montpelier, and he was "well-known for his risque antidotes." Malapropisms aside, the Madison tour was the most informative and energetic of the weekend's tours--an acknowledgment of or compensation for Montpelier's odd status: while Mount Vernon and Monticello have been shrines to their illustrious owners for more than a century, Montpelier was a private DuPont mansion till the 1980s.

It was 2003 before the Montpelier Foundation decided to restore the building to the way it had been when Madison owned it, which meant getting rid of all subsequent additions. When the work was finished in 2008, the house was half the size it had been, the exterior had been stripped of a 150-year-old coat of stucco, and the inside was bare.

Touring the new-old building feels less like stepping back in time (or stepping into a museum exhibit) than like walking through a real-estate open house--less retrospective than prospective. This air of absence makes the fourth president seem more mythic than his taller, more thoroughly enshrined fellow Virginians.

The walls in the parlor are plain splotchy plaster; a new batch of wallpaper, the flocked red velvet chosen by Dolley Madison, is supposed to be manufactured in France this coming summer. Paintings or reproductions of paintings fill some of the wall space, among them a bare-breasted Mary Magdalene recognizable from the parlor at Monticello. The Magdalene now at Jefferson's house, the guide said, is Madison's original, while Madison's house has to make do with a copy.

A near-empty room upstairs, on the front of the house, has a corner fireplace and a single bookcase with adjustable shelves, built by enslaved carpenters. This was Madison's father's library, where the younger Madison drafted up a plan for a government with three branches and a bicameral legislature.

Like Washington and Jefferson, Madison married a widow. He had no children of his own; over the course of his life, he secretly spent $40,000 to pay off the gambling debts of his alcoholic stepson.

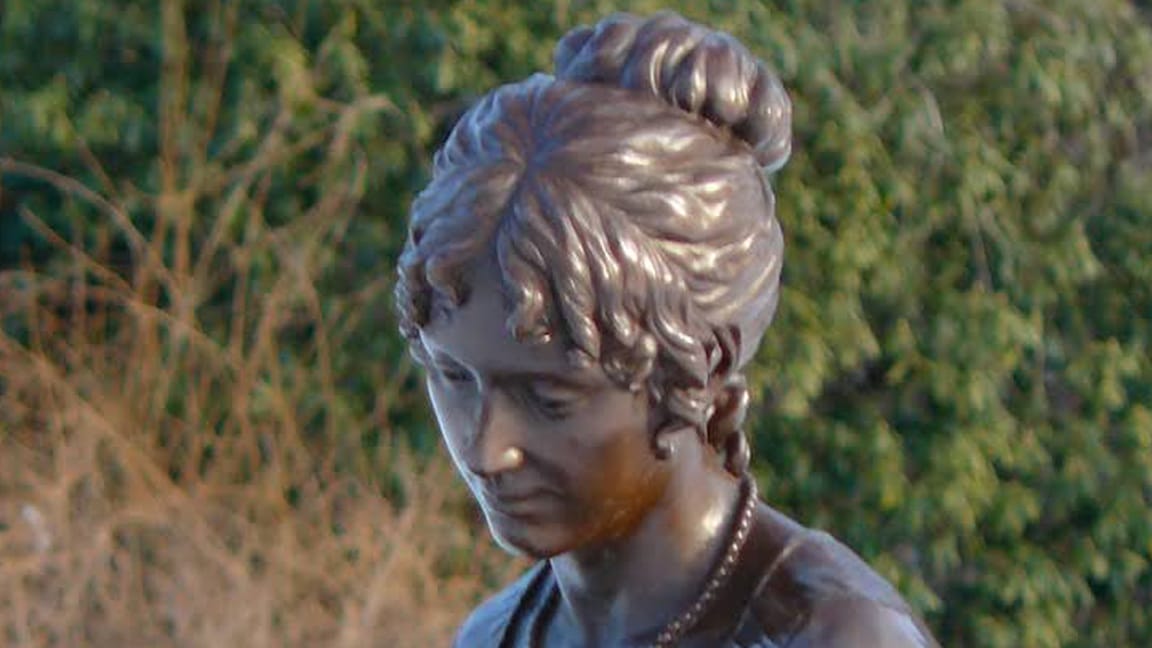

Downstairs is Madison's study, where he spent his final year, too crippled by arthritis to go up to his bedchamber. A life-cast of the elderly Madison, rendered as a bust in Roman garb, stands by the window, frowning over the room. When he was dying in the summer of 1836, the guide said, doctors offered to prolong things so he could die on a Fourth of July, as Jefferson, John Adams, and James Monroe had died. He declined the opportunity and stopped breathing on June 28, with a smile on his face.

Madison's final scene was witnessed by Paul Jennings, an enslaved servant, who recounted it in a memoir published in 1865. (All three presidential-estate tours favored the adjectival "enslaved" construction, as in "his enslaved butler," over the noun "slave.") After James Madison's death, Dolley Madison sold Jennings. He was then bought for $120 by Daniel Webster and freed, after which Jennings worked for Webster and paid back the sale price in installments over the course of 15 months.

Later in life, Jennings wrote, he often visited Dolley Madison—living by then in a "state of absolute poverty"—and "occasionally gave her small sums from my own pocket."

EASY LISTENING DEP'T.

Click on this box to find the Indignity Morning Podcast archive.

ADVICE DEP'T.

GOT SOMETHING YOU need to justify to yourself, or to the world at large? Other columnists are here to judge you, but The Sophist is here to tell you why you’re right. Direct your questions to The Sophist, at indignity@indignity.net, and get the answers you want.

SANDWICH RECIPES DEP'T.

WE PRESENT INSTRUCTIONS in aid of the assembly of a sandwich selected from A Thousand Ways to Please a Husband: with Bettina’s Best Recipes, by Louise Bennett Weaver and Helen Cowles LeCron, published in 1917, available at archive.org for the delectation of all.

Peanut Butter Sandwiches (Twelve sandwiches)

4 T-peanut butter

1/8 t-salt

1 t-butter

1 T-salad dressing

12 slices of bread

12 uniform pieces of lettuce

Cream the peanut butter, add the butter. Cream again, add the salt and salad dressing, mixing well. Cut the bread evenly. Butter one side of the bread very thinly with the peanut butter mixture. Place the lettuce leaf on one slice and place another slice upon it, buttered side down. Press firmly and neatly together. Cut in two crosswise. Arrange attractively in a wicker basket.

If you decide to prepare and attempt to enjoy a sandwich inspired by this offering, be sure to send a picture to indignity@indignity.net.